My Mystery Ships

by Rear Admiral Gordon Campbell, VC., DSO

CHAPTER 1

THE SUBMARINE MENACE

THE Great War produced many inventions, rapidly developed many weapons which were yet in their

infancy, and brought into use forms of warfare which had either been unforeseen or only foreseen in the minds of

men of great vision, who were generally ridiculed at the time ; just as now we have those who foretell how future

wars will be entirely fought in the air and how whole towns and even countries will be destroyed by poison.

Before the war the submarine was a weapon which led to much discussion: some foretold how the

Power that had submarines could destroy whole armadas; others said that the submarine was so vulnerable that a

rifle-shot was all which was required to hit its periscope and destroy it! The fact remains that the submarine

became one of the most, if not the most important weapon during the war, and what was called the Submarine Menace

loomed very large in the many big problems of the war. Apart from other considerations, I don't think many people

realised how far away from their base submarines could or would operate. I remember, one Sunday afternoon in the

Channel, when on patrol in my destroyer, I received a wireless message that a submarine had passed through the

Straits of Dover. This was one of the first war thrills we had had, and I passed the word round with a caution

about an extra smart look-out, but I feel sure hardly a man aboard believed me. They only thought it was a scare

to liven them up The idea of a German submarine breaking through the Straits seemed too incredible to them.

What exactly was the Submarine Menace? The fact that submarines could, under certain conditions,

such as daylight, calm weather, and within easy reach of their base, torpedo and sink men-of-war was well known; and it was also well known that if suitable precautions were taken, if ships steamed at high speeds or alternatively

were escorted by high-speed vessels, then the chances of success on the part of the submarines were remote. Men-of-war

may have been lost because speed was not available and escorts were not supplied, or for other reasons, yet this

was but a reminder of the power of the submarine, and was not a menace to the country. If harbours had proper defences,

such as patrol craft outside and booms at their entrance, then the ships could lie in safety and no submarine could

enter. That important harbours were not so defended is well known, and the defect was remedied rather late. On

the whole, although something of the power of the submarine was realised, yet it was under-estimated, and it is

well known how the Grand Fleet of Britain had to leave its base at Scapa Flow because the defences against submarines

were not sure.

I have no intention of entering on a discussion of International Law, nor, at this time of the

Peace, the question of humanity, but for the purposes of this book it is only necessary to state as a fact that

Germany decided to use her submarines to attack and sink our commerce, the life-blood of the British Isles, the

source of supply to the Grand Fleet in the North Sea and our Armies in France. This was something entirely new.

For long long years Great Britain had been dependent on her commerce, and as long as she is an island this must

always be so, whether it be by sea or air. The protection of commerce at sea was a recognised part of every Government's

policy - as it was essential to the very existence of our island. The protection depended, to a large measure,

on cruisers to protect our commerce against other cruisers or armed liners and raiders. But here was something

different our commerce was subject to attack by an " unseen enemy, to be sunk by a torpedo before any signal

for help could be sent or any escape could be attempted ; liners, tramps, fishing craft, men, Women, children,

were all at the mercy of an " unseen enemy." This, then, was the Submarine Menace.

The severity of the German attack on commerce varied from time to time according to their policy.

Starting rather mildly in 1914, it went through varying stages of intensity ; sometimes " danger zones "

were declared, at other times neutrals were to be spared ; but eventually, on February 1st, 1917, the Germans declared

what was known as the intensified submarine campaign, which meant, roughly, that any ship and every ship was liable

to be torpedoed and sunk without warning. To show the seriousness of this menace, and without quoting a lot of

statistics, one has only to look at the figures for April 1917 - over 545,000 tons of British shipping were sunk,

and together with allied, neutral, and fishing craft the total came to 875,000 tons. This was the worst month,

but the sinkings had been going on since September 1914, slowly but surely, and it looked at one time as if the

submarine would win the war, as it would have been impossible for the country to have continued to sustain such

heavy losses of shipping. How was this menace to be dealt with ? I do not intend to deal with all the many methods

employed, such as mines, nets, auxiliary patrols, hunting flotillas, hydrophones, aircraft, depth charges, destroyers,

submarines, and the surest and best method of all, Admiral Keyes's, when he blocked the submarines in at Zeebrugge

so that they couldn't come out.

All the methods I have just mentioned were offensive ones, and set out to destroy the submarines,

or to stop them coming out, which was the only way of stopping the menace. But nearly all these methods, except

our own submarines themselves, which of course could go anywhere the enemy submarines could go, were more or less

confined to coastal work. This was good as far as it went, but the enemy submarines went farther-they were to be

met anywhere between Archangel and New York, Gibraltar and Port Said-in other words, in waters too deep for mines

and in areas too far afield for the auxiliary patrol, which did such excellent work during the war, to function.

Until the great step was taken of bringing in the convoy system we read so much about in previous

wars, the merchant ships outside of coastal waters

were practically dependent for safety on their own defensive armament. They might occasionally

get a chance of ramming, but this was not frequent ; and by zigzagging, making smoke from specially constructed

smoke apparatus or smoke floats, or following certain routes, they could reduce their chances of being attacked.

As fast as guns could be produced every merchant ship was defensively armed, and how gallantly they used their

armament whenever they got a chance is a story in itself. The chances of a submarine being sunk by one gun, which

was all a merchant ship carried, and this generally a very small one, were rather remote. In fact I don't think

any submarines were actually

destroyed by gunfire from merchant ships, the submarine always having the advantage of being

able to keep out of range, or alternatively to dive. The idea was therefore conceived of fitting merchant ships

as men-of-war, with a specially trained crew aboard and a concealed armament strong enough to destroy a submarine

if encountered. To all intents and purposes they would look like ordinary innocent merchant ships, and would therefore

entice the submarine to them.

This class of ship went under various titles. Their real function was decoying, and the proper

title would, therefore, appear to be " decoy ships," but it was not secret enough. The Admiralty in the

early days referred to them as " special service vessels," and the ships themselves were known in the

dockyards and so on as S.S.-- The fact that a number of people in and about the dock-yards and naval ports knew

that the Master of S.S. -- was a naval officer, that special guns and gadgets were being fitted, and that no one

except on duty was allowed on board, naturally gave ground for them being referred to as "Mystery Ships,"

and I don't think for quite a long while that many people knew what duty these vessels were really employed on,

although of course some must have suspected. Towards the latter part of 1916 the Admiralty gave them all "Q"

numbers, and they became Q-ships. This at once appeared to reduce a large amount of the secrecy of them, because,

whereas special service vessel " or " mystery ship " are terms which have been applied to all kinds

of craft, from battle-cruisers downwards, the term " Q " was only applied to " decoy ships,"

and, in consequence, nearly everyone knew that H.M.S. Q.1 was a decoy ship, just the same as they knew H.1 was

a submarine. During the war " mystery ship " was applied to the " Glorious " class of ship,

the dummy battleships, monitors ; in fact, everything new that had no details published, but whose existence was

roughly known, became a " mystery ship," and might therefore be anything. It was the title I liked best,

and is the one that is used in some history books referring to similar craft in bygone days. The " Q "

title didn't last very long ; in fact, I only had to use a " Q " number for a few months, when names

were reverted to ; but the mischief had already been done, and Q-ships became a well known title.

It must not be imagined that the mystery ships were any invention of the war, as attempts to

decoy the enemy are as old as can be. The hoisting of false colours is a long-standing practice, and it is only

natural that enterprising officers would go a bit farther and disguise their ships and think of additional ruses.

An illustration of this was the famous German cruiser Emden, with her false funnel and friendly ensign, when she

made her attack at Penang.

Only a few years before the war, Lord Charles Beresford, when in command of the Channel Fleet,

deluded his own squadron at night by arranging the lights of his battleship to make her look like a merchant ship.

It may be of interest to refer to some more historical cases of the use of mystery ships, the

chief difference being that in those I shall refer to the ships were built as men-of-war, and their Captains rigged

them and acted so as to appear as merchant ships, and be good bait for the corsairs. In the Great War the mystery

ships were either already merchant ships and fitted internally as men-of-war, or they were specially built to look

like merchant ships.

In 1672 a case is recorded of a Captain Knevet, in command of the Argier, disguising his ship

"by housing his guns, showing no colours, striking even his flagstaff, and working his ship with much apparent

awkwardness," thus deceiving a Dutch privateer off Aldeburgh.

In 1799 we read of a Boulogne corsair coming up with what she thought was a powerful merchant

ship; her appearance, the cut of her sails, and the way they were set all led to this belief. But as the corsair

was running alongside, the batteries were unmasked, and she found herself up against a disguised cruiser with twenty-four

guns.

In another case, in 1803, a French corsair was operating in the North Sea and came across an

English ship, which aroused the Frenchman's suspicion by her shape and the appearance of her canvas. The Frenchman

acted cautiously, and discovered she was a brig trying to imitate a merchant ship to decoy him closer, so he at

once made sail to escape.

In the Life of Admiral Mahan there is a letter he wrote as a midshipman in 1861 suggesting that

a decoy ship be used to deal with the sea-rover Sumter. In order to reduce suspicion, he suggested that a sailing

vessel be used for the purpose.

One of the most interesting proposals for mystery ships is contained in an unsigned letter which

appeared in the Naval Chronicle of 1811 (vol. xxv):

DEAR EDITOR,

" At a period when our commerce suffers such injury from the enemy's privateers, it is the

duty of everyone, if he has any idea of a means by which this loss may be prevented, or materially lessened, to

communicate it. Conversing with a person who had visited the Continent, he mentioned to me that, a few months since,

he was accidentally at Boulogne, when his attention was drawn by several groups of people in earnest and melancholy

conversation. On investigating the cause, he found that two of their privateers had that morning returned, one

with a loss of twenty-eight, and the other of thirty-six men ; that they had in conjunction attempted to board

a merchant brig, which instead of being charged with their expected plunder was conveying troops of some description,

who, rising unexpectedly, made that carnage among them.

" Nothing, my informant says, could equal the dismay and distress that prevailed among this

description of people, and that some time elapsed before they could again man those vessels.

" I confess this information made a great impression on me, from its seeming strongly to

corroborate an idea I had long entertained of the practicability, if not of annihilating, at least of greatly reducing

the number of the enemy's privateers ; and in the number so reduced, of producing that caution and delay which

might possibly facilitate the escape of some of our vessels.

" The plan which has often engaged my thoughts is that two or three merchant vessels, having

as little as possible the appearance of ships of war, or armed vessels, each having on board such a number of men

as may be considered sufficient, well trained to the use of the musket and rifle, should be kept sailing on such

parts of our coasts as are most infested by privateers, and that when attacked by the enemy under a conviction

of they being private vessels, in their favourite place of boarding, our men (who might easily keep themselves

to this period in concealment) might, without difficulty, give them such a lesson as that which the two privateers

I have before mentioned received.

" The system of attack on privateers of the description that infest the narrow parts of

the Channel, to be effective, must be by boarding, as in any other they might be kept in bay by a single 12-pounder.

" That some inconvenience may attend the execution of such a project I can conceive, but

I am not aware of any at all commensurate with the benefit I should anticipate from it. This kind of service may

be said to be full of hazard and danger, and that those engaged in it cannot be rewarded by the capture of the

enemy's vessel.

" With regard to its danger, I think it would only have enough to take off the tedium of

the service. I imagine it would not in reality be great. The vessel's bulwarks might be made musket-proof, and

during the short period of attack our men would be engaged under so many advantages, that the hazard could not

be of great consideration. To compensate them for having a miserable mutilated crew in possession of their vessel,

they might be handsomely rewarded for each vessel repulsed that attacked them. As soon as it was conjectured that

the enemy would be able to particularise the vessels in question, they might be either new painted or changed for

others with little inconvenience." It is curious how near to a description of our mystery ships in the Great

War this letter comes.

It is quite obvious, then, that the idea of trying to decoy an awkward enemy did not originate

in the Great War ; but whereas most of the previous examples appear to have been actions taken on the initiative

of the officers commanding "on their own," during the Great War

became part of the Admiralty policy, though it is quite clear that the freer the hand given to an officer commanding

such a ship, in selecting her, in fitting her out, and in his methods of fighting, so much the better. No hard-and-fast

rules can be laid down, or text-books produced, as to the methods of fighting or the " bluff " to be

used. It must be entirely in the hands of the Captain of such a ship. Secrecy was a matter of the most vital importance,

and here again a Captain of a ship might think of some new form of decoying his enemy, but it was not always wise

to let anyone outside of the ship know anything about it. A Captain, to carry out his intentions, might want a

special class of ship or some special gadgets, and so it would appear the soundest scheme to select the officer

considered suitable for the job and then let him find and fit his own ship with as much carte blanche as possible.

The German submarines' attack on our commerce included everything, from liner down to the innocent fishing vessel-nothing

was spared. And some of every class of vessel were fitted as mystery ships in consequence : liners, tramp steamers,

semipassenger steamers, coastal steam colliers, steam trawlers, schooners, barquentines, ketches, smacks, luggers,

and convoy sloops. The liner type of mystery ship only had a short life, as it was extravagant, and could not easily

be spared for the service.

It was rumoured that the Captain of one of the Liner decoy ships asked for a party of extra men,

as he pointed out it was necessary for part of his disguise to have some ladies as passengers. The reply he got

was approval, provided the men were only disguised as females down to their waists!!

Whether the yarn is exactly true or not, the idea is quite sound, as whatever you pretended to

be had to be done thoroughly or not at all. In the same way a fishing smack should have a cargo of fish, live or

dead, on deck to make her "smelly " and attract the seagulls, as one invariably sees the seagulls hovering

round to harbour.

These mystery ships had a great advantage over the many other " anti "-submarine vessels, in that they

could, except for the smaller type and fishing smacks, operate anywhere ; and these, together With our own submarines,

were the chief offensive methods outside of coastal waters. It is true that the destroyers did take offensive measures

outside of coastal waters, but unfortunately there were not enough of them. They were such a useful class of vessel

that everybody wanted them, from the Grand Fleet downwards, and there were never enough to go round. In consequence

they were generally tied down to escorting a particular ship or convoy. And I should think they were the hardest-worked

ships in the war, for on them depended to a large extent the safe arrival of the great convoys in England and France.

A disadvantage they suffered was that they did not carry sufficient coal or oil to allow them to stay at sea very

long, but they had the great asset of speed, which enabled them to rapidly close the enemy and drop depth charges.

The sailing decoy ships, such as the famous ship Prize, a schooner of 227 tons, commanded by

Lieutenant Sanders, V.C., R.N.R., were a very attractive type, as somehow or other a sailing vessel always looks

such an innocent thing, dependent on the elements of nature to take her from place to place, sometimes making a

fair speed and sometimes becalmed. The Prize was fitted with an auxiliary engine, which enabled her to get to the

place she wanted to under cover of darkness without too much delay. But her very size and propelling power naturally

limited her radius of action.

All types of mystery ships were necessary and useful, but I think the most useful type of the

lot were the good old tramp steamers, which could go anywhere, be seen nearly anywhere, and had a seagoing capacity

of anything up to twenty-four days.

They are the most common type of ship met with at sea, and, carrying as they do from 5 to 10,000

tons of cargo, they were just what the submarines most wanted. Every other type of craft, except the tramp mystery

ship, had limitations to their sphere of activity. The liner would be out of place on certain routes, the smaller

craft were naturally confined to certain areas, both by virtue of their calling and their stowage of fuel. Even

our own submarines were hampered to the extent that arrangements had to be made for their safety.

In the early days of the submarine warfare mystery ships were used rather sparingly, and it was

not till 1916-I7 that they appeared in any large numbers, and by that time some of their usefulness had already

gone. It is fairly obvious that if you are going to try deception on anyone, the greatest secrecy is necessary,

and once you have been " bowled out," the other party is for ever suspicious, and so with the mystery

ships (and I believe also, the Tanks), they were used in small numbers at first ; but owing to unsuccessful actions,

the fact that we had mystery ships became known, and when produced in large numbers the best opportunities had

passed, and success for the mystery ship became extremely difficult.

The first two mystery ships to be fitted out were the British ship Victoria and the French ship

the Marguerite - both at about the same time, November 1914.

One of the great difficulties of mystery ships was to keep their existence secret, especially

during the " fitting-out " period. This was perhaps not so difficult for the ships fitted out at Scapa

by Fleet labour, as there was not a great deal of mixing with other ships ; but when it came to fitting out in

a dockyard port in the South, it became a far more difficult matter, as I will relate later, it being obvious that

a large number of people must be in the know.

A variation of what might be called the plain mystery ship was a combination of a mystery ship

and a submarine, the two working together, with either the submarine actually in tow submerged and connected by

telephone to the surface ship, or acting in company by a prearranged system of signals. The idea in this case was

for the surface ship to attract the enemy submarine, and then, on communicating with our own submarine, the latter

would go off and torpedo the enemy. This method secured the very first success of " decoy " on June 23rd,

1915 when the disguised trawler Taranaki, under the command of Lieutenant-Commander H. D. Edwards, was towing submarine

C.24, under command of Lieutenant F. H. Taylor. They were cruising off Aberdeen, when a submarine U 40 was sighted.

Difficulty was experienced in slipping the tow, and eventually C.24 had to make his attack handicapped by having

the tow-rope hanging from his bows and the telephone cable fouling his propellers, but he succeeded in torpedoing

the enemy. This success was followed soon after by another on July 20th, 1915 when the trawler Princess Marie José,

under command of Lieutenant Cantlie, RN, was towing submarine C.27, under the command of Lieutenant C. C. Dobson,

R.N. They met a submarine, and whilst the Marie José was engaging in action, C.27 slipped the tow and torpedoed the enemy submarine U.23.

The first success scored by a mystery ship on her own was on July 24th, 1915, by the Prince Charles,

a small coastal steamer of some 400 tons, commanded by Lieutenant Mark Wardlaw, which sank her submarine off Roma

Island. She was one of the vessels fitted out at Scapa. This was followed by two successful actions of the Baralong

in August and September 1915.

At the time I started on this service in the Loderer there were only two of us for working in

the Atlantic and approaches to the Channel, the other one being the Zylpha, commanded by the late Lieutenant-Commander

Macleod. Two smaller ships joined a little later, the Vala (Lieutenant-Commander Mellin) and Penshurst (Commander

Grenfell). This latter, a tramp steamer with the funnel aft, was one of the best mystery ships of the lot, but

was unfortunately lost in a gallant action when Lieutenant Naylor was in command.

All four of us were tramps, the Loderer and Zylpha being ships about 3,000 tons and the Vala

and Penshurst about 1,000 tons. The only survivor of this quartette was the Loderer, but they all played their

part in helping to cope with the great menace.

In the following chapters I am going to give my own experience of this form of warfare, and although

I have been able to quote here previous successes, yet I, at the time, knew nothing about them, and had only heard

the vaguest yarns of mystery ships being in existence.

To find the inventor of "mystery ships" one must obviously go back to 1672, or even

to the days when Eve decoyed Adam.

CHAPTER II

THE U-BOAT PROBLEM

Before attempting to describe the methods employed to bring about the destruction of the enemy

submarine by mystery ships, it is as well to explain briefly the former's capabilities, limitations, and their

various methods of attack on merchant craft. Many types of submarines were used, differing greatly in size, radius

of action, and other details. They were classed as U-boats, U.B. or U.C., and carried numbers, 1, 2, 3, etc. They

all carried torpedoes, and they nearly all carried a 4.1-inch gun. The U-boats were the largest ones: they could

go nearly anywhere, in fact were submarine cruisers, and eventually carried two 5.9-inch guns in addition to torpedoes.

It was this class of boat which, visited New York, Madeira, etc. The U.B. boats were a smaller type which operated

chiefly in the North Sea, and the U.C.-boats were those that mainly carried mines, which were laid around our coasts,

but they also went quite far afield to use their torpedoes.

A torpedo, nicknamed a "tin fish," is a, wonderful under-water weapon, running on its

own power of air and carrying a large charge of high explosive. It would be aimed at the ship, and if successful

in hitting (depending on many details I do not intend to go into) it would make a hole some 40 feet square, and

in the case of an unprotected merchant ship would in all probability cause her to sink, according to her size,

cargo, and build. The torpedo, travelling through the water some 10-20 feet under the water, would leave a bubble

track on the surface. This, if seen in time, would frequently enable a ship to avoid the torpedo, as the torpedo

once fired would (or should) maintain a straight course, just as you can dodge a brick coming at you if you we

it in sufficient time by turning one way or the other, so could a steamer dodge a torpedo. For that reason a submarine

would fire from as close a range as possible, though he would have to be careful not to get so close as to run

the risk of damaging himself by the resulting explosion or of being rammed, both of which sometimes happened.

The submarine has the great power of invisibility, which can enable her to make an unseen attack or to make a rapid

disappearance if discovered ; but in her role of an unseen assailant she could only attack a ship with torpedoes,

her sight being given her by the periscope, which would be above the water for such length of time as was required

for making her attack. The periscope, by revolving it, enabled the submarine to see distinctly all that was going

on around her; but the officer looking through it would only be able to look in one direction at a time. This is

important to remember. A mystery ship, not knowing in which direction the submarine officer was actually looking,

always had to assume he was looking in all directions. If the periscope was sighted, which would only be likely

under ideal weather conditions, and a shot fired at it, the chances of it being hit were practically nil, as it

only looked like a small spar sticking a foot or two out of the water, and even if a lucky shot got it, it made

no difference to the submarine, as a second periscope was available.

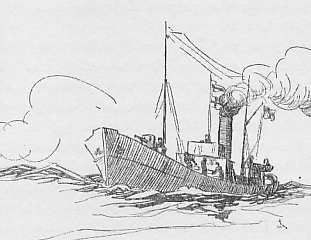

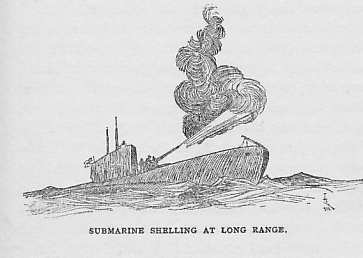

Another form of attack was by gunfire, but to carry this out meant that the submarine would have

to come to the surface and expose her conning tower and upper-deck casing, but not necessarily her pressure hull

- the most vulnerable part. The target would still be very small and difficult to hit. On first coming to the surface,

a submarine's conning tower would be closed, and probably her pressure hull would be just under water. The only

target worth hitting would be the conning tower, and, unless hit by the first round or so, she would be able to

dive in seconds and get away. Even if the conning tower was hit by the first shot; it did not necessarily destroy

the submarine, as a watertight door at the bottom of the conning tower could be closed and the submarine remain

watertight.

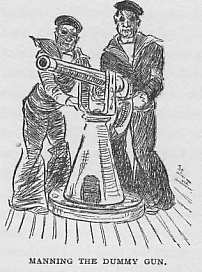

Before the submarine could open fire with her gun, it of course had to be manned, and this meant

that the lid of the conning tower had to be opened to enable the crew to get along the deck to the gun, and for

this purpose she would have to come right to the surface. Now, this condition laid her more open to destruction,

the target was a better one, a hit on the conning tower might prevent the lid being closed and the submarine submerging,

and the confusion likely to be caused by the gun's crew rushing back and getting inside again would give the attacked

ship a longer time to fire. Even under these conditions the hits would have to be obtained within a minute or so.

A case occurred during the war where the conning tower had been hit, the Captain and others taken prisoners, yet

the submarine managed to get back home, the lower door presumably having been closed and the men on deck sacrificed.

This case will give some idea of the difficulty of actually destroying a submarine by gunfire.

A third method of attack a submarine could make on a merchant ship was to come to the surface,

order the ship to stop, and then, after ordering the crew to their boats, bombs set with time fuses could be placed

on board or the inlets to the sea opened. This, of course, could only be done if the ship was unarmed.

As this book chiefly deals with the submarine attack on trade outside the North Sea, we need

only follow the proceedings of the U and U.C. types. It is sometimes imagined that submarines continually cruised

under water and seldom came to the surface during their voyages from their home ports to their ambushing positions.

This is quite incorrect; in fact, they seldom submerged on passage, and never if they could avoid doing so, because

we come at once to one of the submarine's great limitations, that of electrical power. Her means of propulsion

when submerged are electric motors run off large storage batteries, which are extremely heavy and bulky for their

power and life. In consequence, they are constantly requiring to be recharged, which necessitates the submarine

being on the surface. When a submarine is submerged, it is almost impossible to get such a perfect trim that she

will keep her depth without using the motors. Thus, unless the submerged submarine is lying on the bottom, she

is constantly drawing on her vital reserves of electricity. When these are gone, she is compelled to come to the

surface to recharge her batteries. Even when lying on the bottom - and this is only possible in certain localities

and in fairly shallow water - a certain amount of electric current would still have to be used for lighting, cooking,

and heating.

It will be seen, therefore, that a submarine would remain on the surface as long as she could,

and on her voyage to and from her hunting-ground she would not be greatly affected by the limitations referred

to, as she would always cruise at night on the surface and nearly always during the day. As soon as she sighted

anything by day, she submerged until the danger was passed. The exhaust gases from the Diesel engines are led out

below the surface of the water, and cause practically no smoke to give her away ; on the other hand, the submarine

could always locate a surface craft by the tell-tale smoke over the horizon long before she was herself sighted-always

provided a good look-out was being kept. Thus it was practically impossible to deal with enemy submarines on passage

from one place to another, if they wished to avoid detection, except by such means as mines, or in areas such as

the Irish Sea and Dover Straits, when hunting flotillas could harass them and make them draw on their vital electricity.

It is true they were sometimes sighted when on passage, or their presence might be given away

by the use of wireless ; but all reports of "sightings," especially of periscopes, had to be treated

with a certain amount of suspicion, unless confirmed by something authentic, as it is extraordinary how many "periscopes"

you think you see when day after day you are straining your eyes looking for them. Casks, wreckage, navigational

buoys, whales, black fish, our own M.L.s and the American chasers - in fact, nearly everything was reported at

some time or another as a "conning tower" or submarine.

The mystery ship's best chance, therefore, would be to cruise in the places where submarines

were operating, and not waste much time on an odd chance during their passages ; these places generally would be

on the main traffic routes, the entrance to the English Channel, and focal points. When the convoys started - which

meant nearly all ships had destroyer escorts on approaching land - it was advisable to get farther afield, but

this will be referred to later.

We will now assume the submarine commander has got into the traffic, and he would probably have

a fairly large area in which he intended to operate, as on each occasion of his attacking a ship, whether successfully

or otherwise, he would know that signals reporting his presence would be sent out, which would have two effects,

one to bring patrol craft to the spot and the other to divert other ships from the locality, so for these two reasons

he would go elsewhere, to avoid being harassed and to have a chance of getting the diverted ships. For this reason

it was no use a mystery ship going to a place where a submarine had been: you had to go on a track you thought

he might be going to. When operating, he would still keep on the surface as much as possible, not only for the

reasons already given, but also to increase his are of visibility, but he would, anyhow in daylight, be trimmed

ready for an instant dive. On sighting smoke, his first move would be, as before, to dive to periscope depth, about

23 feet. In this condition the whole of the boat, pressure hull, gun, and conning tower were, of course, invisible,

and the submarine could either raise one or both of his periscopes above the surface a few feet or lower them below

it.

When the steamer came over the horizon, the first thing the Captain of the submarine wanted to

discover was what she was, her course and speed. Unless the course of the steamer was going to take her fairly

close to the submarine, there was no hope of getting in an attack by torpedo ; this was because the speed of the

submarine when submerged would be very slow, perhaps not more than 4 or 5 knots, and he would want to get inside

of 2,000 yards to fire. However, if things looked favourable and the quarry was coming well down towards the ambush,

the submarine would manoeuvre to get a few hundred yards away from the track the steamer would pass by, and then

wait his moment. In the meantime the periscope would be raised for a few seconds at short intervals, to cheek the

steamer's course and speed, as accurate knowledge of this was essential if the torpedo was to be sent off to hit

it. The fact that the periscope had only got to be used for a few seconds at a time made it extremely difficult

for the steamer ever to sight it ; and on the other hand, if the steamer was zigzagging, especially with a good

turn of speed, it made it very difficult for the submarine to gauge the course. If all went well from the submarine's

point of view, the torpedo would be fired when the victim was nearly at her most vulnerable condition, one hit

on the pressure hull being all that was required for his destruction.

The submarine attack by gunfire had the advantages that he would be on the surface, and therefore

in favourable weather would be able to go at as good a speed as the average surface merchant ship, and could overtake

the slow tramp and sailing vessel. If the ship was unarmed, there was nothing to fear, and it would be soon reduced

to abandoning ship ; if the ship had a defensive gun, it would then be necessary to keep out of range, and as the

defensive guns increased in size so the submarine guns increased, and the large submarine which came out at the

end of the war with their two 5.9 inch guns were a very serious problem. Had they come out earlier, defensively

armed ships and mystery ships would have required 6-inch guns. By the time they did come out the mystery ships

were nearly dead.

The last method of attack referred to - that of putting bombs on board or opening the valves

was, of course, the cheapest in every way, and was frequently used at one time. The submarine ordered the ship

to send her papers over first, but as already mentioned, the submarine had to be sure the ship was unarmed, and

it soon became obsolete except perhaps for neutral ships.

It will be realised from the foregoing that when the secret of the mystery ships became known,

then the submarine had to think twice before coming up to ask for papers or fire his guns, and the mystery ship's

attempt to decoy him also became more difficult, which will be clearly brought out later.

The methods employed by the ordinary merchant ship when steaming alone, which were, of course,

used as necessary by the mystery ships, were in the first place to attempt to ram, but this was only done if the

submarine was definitely making an attack on the ship, and such opportunities were very rare. If the ship was unarmed,

the only thing to do was to attempt to escape by steaming away, if possible head to sea, so that if the submarine

followed he would have difficulty in firing. Even if armed, attempt at escape would be the best way to safety,

as the submarine invariably had a better range than the steamer and most certainly a better target. Ships were

also fitted with smoke floats and smoke apparatus, which in favourable winds facilitated their escape. But when

the convoy system, which meant that ships sailed in groups under man-of-war escort, commenced, other methods of

protection and safety were more readily available and the day of the mystery ships were nearly over.

CHAPTER III

FITTING OUT

October 1915

In September of 1915 I suddenly found myself out of a job. I had been Lieutenant in command of

an old 30-knot destroyer, Bittern, and had been working from Plymouth, escorting, rescuing ships, going on wild-goose

chases after submarines which frequently turned out to be black fish, and all odd jobs. At last one day we thought

we had really met an enemy ship. She looked suspicious and refused to answer our signals. I therefore gave chase

and told the chief engineer to get every ounce of power he could, with the result that we steamed back to harbour

on one engine at four knots! The suspicious vessel turned out to be a new seaplane carrier doing trials, we had

burst our engines, and had to pay off.

I had applied for a destroyer at Harwich or a gunboat in the Persian Gulf, anywhere that there

might be some "scrapping," but a more exciting job was in store for me. Over a year in the English Channel,

without sighting the enemy or smelling powder, had made me restless, and I had visions of the war ending without

firing a shot. The idea was particularly galling, as we were continually escorting our gallant troops on their

way to the fighting line and also seeing the wounded returning in the hospital ships. I was sent for at the Admiralty

and asked if I would like to go in for some " special service," but was not given any details, except

to be asked had I heard of the Baralong, and told that I should have to serve under Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly. Although

I didn't know Admiral Bayly personally, I knew his reputation for being a man who understood war and would tolerate

neither fools nor red tape in fact, a man to serve under, especially in wartime. I had also heard faint rumours

of one or two mystery ships in the Channel, and without a minute's hesitation I accepted the "special service."

I felt myself thoroughly fortunate, as I was fed up at the thoughts that the war would end before

a chance of a " scrap " came. As I left the Admiralty someone said to me, " Well, Admiral Bayly

will probably either make you or break you in your new job." What more could one want in wartime.

My only instructions were to proceed to Devonport, where I would find a collier called the Loderer.

On arrival at Devonport I awaited the arrival of the ship from Cardiff. She arrived a few days later, well filled

with a cargo of coal. My first impression was, " Fancy commanding a thing like that!" She looked at first

glance thoroughly filthy inside and out, but she also looked a typical tramp, and the more I thought of what our

game was to be, the more I got to like her and feel that she would be an excellent ship for the job. After her

arrival I received verbal instructions from the Admiral Superintendent of the Dockyard to "fit her out,"

and had placed at my disposal three 12-pounder guns and a Maxim. I was given a free hand as to how I proceeded,

and could ask for anything I wanted, except guns, which at this period were somewhat scarce. I think the independence

of the job was one of the great attractions of mystery ships ; it was not like going to a ship which is already

built on a more or less standard pattern and carrying out a well-known routine. Here was something "out of

routine," and every thought was directed to dealing with new problems, some simple of solution and some extremely

difficult.

I don't think I was ever actually told I was to go "hunting" or "decoying"

submarines, but my raison étre seemed fairly obvious,

and the less said the better, secrecy in a job of this sort being of vital importance, for if the enemy got to

know of our existence and had a description of us, all attempts to decoy him to destruction would fail.

My idea, therefore, was to fit out the ship as a man-of-war, but with the outward appearance

of an ordinary tramp steamer which would plough the ocean with a cargo of good things.

At the same time arrangements must be made so that as soon as the enemy had been decoyed to the

required position, the disguise could be thrown off in a few seconds on the order "open fire" being given

and the man-of -war revealed in deadly earnest.

Before starting I "took over" the ship from the Master, much to his disgust, as he

couldn't make head or tail of it. It was naturally rather extraordinary to him suddenly finding a naval officer

coming on board and saying he was going to take command of the ship. He was very sporting about it, and I think

may have had an inkling of something of what was on, as after all it would obviously be some fighting stunt. He

volunteered to remain and serve under me, but I declined the offer, as I thought it would probably prove uncomfortable

for both of us, especially as he was no longer a young man. Before taking over I told him to send for the Shipping

Master and discharge all his crew. As they had only signed on at Cardiff a few days previous, they were none too

pleased either. The discharge of the crew and the taking over from the Master occupied a day or two, but it gave

me time to look round and think out a few details. There was a certain amount of difficulty in taking over, as

the Master had no detailed order from his owners about his stores, etc., and I had no authority to buy non-naval

stores, especially provisions, from him. We got over most of the difficulties, as I was anxious to have everyone

out of it and get on with the work. The chief difficulty was the ship's supply of wines and spirits, not a great

quantity. Eventually I agreed to the Customs locking it up aboard with their seal till the owners removed it. A

few days later it was reported to me that some men working aboard were found drunk. I at once went to the lockers

and found the Customs seals had been broken and several bottles removed. I, of course, would be held responsible,

and after quiet inquiries as to what fine I was liable to, I bought all the stuff from the owners and entered it

as one of H.M. ships.

The ship was the ordinary type of tramp steamer of 3,200 tons, 325 feet long, and a beam of 45

feet. Although not specially fitted to carry coal, she was loaded with over 5,000 tons of Welsh coal, and her Plimsoll

mark was below that allowed for winter months. The fact that she was not fitted with ventilation for carrying coal

was in due course to put us in rather a tight corner. She was a very old ship in every way, and her maximum speed

was barely 8 knots. According to her official record, it was supposed to be 8.5, but that was many years previous.

I was lucky in having for my First Lieutenant, or, as I now had to call him, Chief Officer or Mr. Mate, Lieutenant

W. Beswick, R.N.R., of the Blue Funnel Line, who came on with me from my destroyer. He had a full knowledge of

tramp steamers and was able to advise and help me in the many details of which the average naval officer is ignorant.

I was also greatly assisted in this and my other ships by Mr. W. T. Mason (Constructor), Mr. Freathy (Foreman),

Mr. Sitters, and a large number of other skilled and for the most part enthusiastic men of Devonport Dockyard.

And last, but not least, Mr. Oliver, of the Naval Store Department, who provided all the fancy stores and things

we required. The ship's fitting out being a little out of the ordinary run of dockyard work at that time, I suppose

more interest was taken in us than I had been used to.

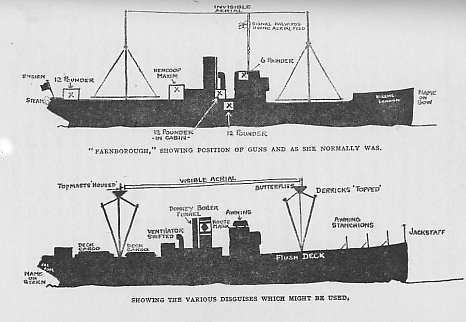

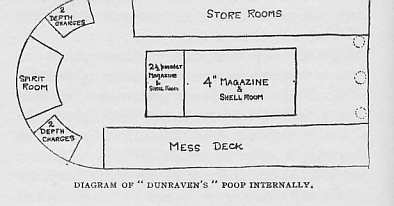

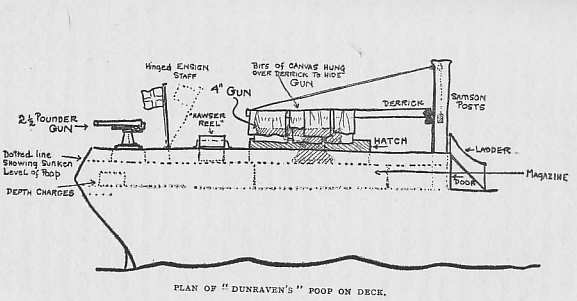

The first decision to be made was the position of the guns, which were placed as shown in the

diagram. The largest gun, a 12-pounder, 18 cwt., was placed right aft in a specially constructed house which represented

a steering engine-house. A small steampipe was led aft from the real steering engine, which was amidships, and

taken over the stern. This, with steam continually puffing out, added to the belief that the house contained an

engine and not a gun. The three sides of the house were all hinged half-way down, and only the back or foremost

end and roof were fixtures. The centre shutter was connected to the ensign staff, and so arranged that when the

shutters fell, the ensign staff, together with any ensign that might be flying, automatically came down before

fire could be opened. All the shutters were so fitted that they would have fallen outwards unless held up, so that

by connecting a wire to them all and bringing it to a "slip" inside the house, all that had to be done

when the order to "open fire" was given was to knock the slip off and the gun was in action a few seconds

later.

There was one great difficulty in the building of this house, as it had to be erected over the

steering gear, which was a very old-fashioned chain arrangement. And the hand-steering gear had to be sacrificed

altogether. Had I realised what we were in for, in the way of weather and the rottenness of the chains, I should

never have agreed to it. At the time we could think of no better arrangement, and so the house was built, the floor

being made movable so that at a pinch (which became necessary) we could steer with "relieving tackles."

It was essential to have one 12-pounder in the centre line of the ship, so as to give us a broadside

of two guns each side. It would, of course, have been better still to have had all three guns on the centre line

and had a triple gun broadside, but this was quite impossible, owing to the structure of the ship and the difficulty

of disguise.

The other two guns, 12-pounders, 12 cwt., were placed on each side of the main deck, the sides

of the ship being cut and hinged. The hinges were outboard, and had to be covered with rubber and made to look

like a rubbing strake for going alongside a jetty. The ports were kept up by a bolt and pin, the guns being placed

fore-and-aft against the ports, and, like the guns in the house, these could be brought into action in a few seconds,

the risk being taken of keeping the guns loaded, with the off`chance of firing into oneself. This arrangement again

was a very poor one, but I was an entire novice at the game. The rubber on the ports caused a lot of trouble and,

apart from the action of the sea, generally got loosened after the ports were opened for gun practice.

When I say the arrangement was very poor, I am speaking from after-knowledge. As a matter of

fact, they passed the test and sank two submarines, as will be related later, but the wheel-house and these gun

ports would have given the whole show away any time after the middle of 1917, when mystery ships were well known.

The Maxim gun was placed in a hen-coop on the boat deck near the funnel. The hen-coop, which was covered on top

with light tarpaulin, was hinged half-way down, enabling the Maxim to be brought rapidly into action on either

side of the ship. Together with the Maxim were also some rifles. As it happened, in February 1916, when at Haulbowline

and before the ship had been in action, I was able to raise another couple of I 2-pounder, 12 cwt., guns and two

6-pounders. Even history does not relate how I got them. The raising of a crew to man them was a more difficult

matter. The two 12-pounders were placed on the upper deck, one each side in "cabins." The cabins were

built on to the existing cabins and fitted with dummy scuttles or ports, which could be used as look-outs. They

were built of steel, and the sides were hinged to fall outwards, the guns being close up to the sides as on the

main deck.

The two 6-pounders were placed one each side of the bridge, the corners of the bridge being hinged

together with the bridge screens, and easily pushed aside before opening fire. These guns were the only ones which

were visible to the ordinary person walking about the ship, and so had to be taken down in harbour or when a pilot

was coming on board. One of the difficulties of fitting these guns in odd places, in a ship not built for the purpose,

was the strengthening of the deck to take the mountings; and this point had to be taken into consideration in selecting

the positions, as they had to be in place where you could get underneath fairly easily for the strengthening and

supports.

The next consideration was messing accommodation and communications. The. ship was in a filthy

state when we took her over, and we had to take everything movable down and have the whole place fumigated, and

a great number of articles, such as bunks, burnt, before I would allow anyone to live on board. The ship was only

fitted to carry about 6 officers and 26 men, but eventually we had to find accommodation for ii officers and some

56 men. The officers' quarters were immediately beneath the bridge, and a trap hatch was cut to enable speedy communication

between the bridge and "saloon," and to avoid too many officers being seen on the bridge ladders. The

engineer officers' cabins were near the engine-room, and the deck officers' near the bridge or guns. The stokers-or

firemen-lived under the forecastle head as in an ordinary tramp; they had bunks instead of the usual hammocks which

the seamen had, and were fairly comfortably off.

On the main deck, under the officers' quarters, an upper cargo space was cleared and made into

a mess-deck for the seamen ; this was connected by an alleyway through the coal the whole length of the ship. The

guns on the main deck adjoined the mess-deck, and so were easily manned, but the guns in the "cabins"

and the "wheel-house" and hen-coop had to be approached through the alleyway and up through trap hatches.

This enabled all the crew to move about between their action stations and mess-deck without coming on deck and

being seen.

Each gun had a good supply of ready ammunition, the reserves being in lockers on the mess-deck,

always a source of danger in the event of being torpedoed or shelled. It was practically impossible to arrange

for any supply of ammunition to the two 6-pounders on the bridge from the magazines (lockers), as it would be seen

being carried up. So they were dependent on what was placed ready for use round the gun. In fact, this really applied

to all the guns, as a submarine would almost for a certainty either have escaped or been destroyed before all the

"ready-use" ammunition could be used. Every position in the ship was connected by voice-pipe with the

bridge, and an electric bell at a later date was also fitted to give the "alarm." Telephones were suggested,

but I decided to reduce electrical gadgets to the minimum and found voice pipes and percussion firing more fool-proof

and reliable. I was, according to my Admiralty scheme of complement, going to have no men with any special electrical

knowledge amongst my crew, and I might have been badly let down if I had "break downs" and no one to

make them good.

The messes were made as comfortable as circumstances permitted, and as cleanliness is part of

comfort, I had them well painted out and kept up to man-of-war standard. Smoking was allowed at certain times but

regular " rounds " were carried out. This meant that every morning and evening Mr. Mate would go round

and inspect the living quarters and everything had to be tidied up and cleaned. On Sundays I would do the inspection

myself.

Although sometimes at sea the "rounds" became impossible owing to circumstances, I

always made a strong point of them, both for the sake of discipline and the men's own comfort. The officers all

messed together, unlike the ordinary steamer, where the Captain is sometimes alone and the Engineers have a separate

mess from the deck officers, as, although the Frothblower had not come into being yet, I knew it was a case of

" the more we pull together..."

This was accentuated by the fact that, not being shown officially anywhere as one of H.M. ships,

neither officers nor men received any share of the gramophones, books, clothing, papers, etc. which kind people

used to send the Fleet, and we had to be entirely dependent to find and make our own recreations, which included

a gramophone and quite a good concert party, which I thought a very good effort for a small ship's company.

As merchant ships of this type seldom had wireless in those days, it was therefore necessary

to disguise the wireless aerial. This was done by having it fitted as an ordinary single stay or wire between the

two masts, the feeder to the wireless room coming down through the upper-bridge like a pair of signal halyards,

real ones being also, fitted.

A sad calamity nearly happened through this one day, for I was only just in time to stop a pilot

bending his pilot flag on to the wireless halyards, and as a message was being passed at the time he would probably

have been electrocuted. Anyhow, it showed the disguise was good, and the pilot never knew what a narrow squeak

he had had. A wireless house had also to be built as near the bridge as possible, and so we put it under the chart-room,

so that direct communication was possible for getting signals through rapidly. I was greatly helped in the wireless

arrangements, which were of a novel type, by a man from Marconi's, Mr. Andrews, who had joined the R.N.R. and served

throughout with me. He had already had experience on the East Coast which came in useful.

There were no proper store-rooms on board for provisions, and these had to be kept on the main

deck, nor were there any heating arrangements - or refrigerators. Inasmuch as the ship was employed in both hot

and cold climates, it will be appreciated that she was not very comfortable. The only bath on board was the Captain's,

and then hot water was only available when there was steam on the whistle (siren)!

Our ship's outfit was now nearly complete, except for some small depth charges, which were kept

hidden away on trolleys ready to be run along to the stem and thrown overboard, a depth charge being a sort of

bomb which explodes under the water at any reasonable depth it may be set to. These were a product of the war and

naturally improved as it went on. The ones we had on this occasion were quite small, of about 100 lb. of T.N.T.,

but eventually they got to some 300 lb. They would have to be dropped very close to a submarine in order to destroy

it, but the moral effect on a submarine crew of having bombs around it may easily be imagined, as the lights might

be put out or the "trim" altered.

An example of this came`my way later on in the war when I had a light cruiser in the Irish Sea.

A submarine had appeared three mornings running, in exactly the same place in the vicinity of Dublin. I therefore

concluded he was lying on the bottom and going full speed across from Holyhead I sprinkled the area with sixty

300-lb. depth charges, and the submarine started his homeward journey that night, having done no damage!

The ship was now fitted for cruising and fighting, but other things had to be thought of. To

an experienced eye it is seldom that two ships look exactly the same: there is generally some slight difference

even between sister ships; perhaps it is the rigging, or the arrangement of the boats or awning stanchions, and

other small details. The importance of the point could not be neglected, as it was well known that a number of

the German submarine crews were men of the Mercantile Marine themselves and had probably been English Channel pilots.

Their seaman's eye would soon spot all the details of a ship. This had to be remembered and arranged for. I have

already explained in a previous chapter how a submarine could see without being seen, and how his best chance of

attack was near the focal points. It is, therefore, obvious that a mystery ship cruising continually in the same

waters would soon arouse suspicion if sighted more than once, perhaps steering north one day and south the next.

As one could never know definitely whether a submarine was in the vicinity or not, we always worked on the principle

that we were always being watched during daylight hours ; so, when working in the same area for days on end, the

appearance of the ship was changed each night after dark. If the ship was on a steady course, say from Plymouth

to Gibraltar, the disguise was not necessary except in the event of an unsuccessful action.

In the early days this was a comparatively simple matter, as ships displayed their own funnel

and house marks; so, with a good supply of paint and with ready-made frameworks of all shapes, diamonds, triangles,

etc., we were able to belong to a different company each day, or as often as necessary. But in 1916 nearly all

British ships were painted alike and showed no distinctive colour on their funnels, nor flew any ensign, so this

disguise was of no further use.

Another fairly simple disguise was to fly neutral colours, a very old and perfectly legitimate

ruse de guerre, provided the national colours are hoisted before opening fire. This disguise necessitated carrying

the suitable ensigns, special lights for night, and big boards with the neutral colours painted thereon for fitting

over the ship's side. During the late war, in which the submarine warfare against merchant ships was quite a new

feature, the flying of "colours" was not sufficient, as it was frequently difficult for the submarine

to distinguish them, and so most neutral ships had their colours painted on the ship's side. Consequently, if one

was "representing" a neutral, the colours on the sides were necessary as well as the ensign. We therefore

had these boards made, which fitted into slots on the ship's side. Canvas screens were also fitted rolled up above

them and became unfolded when the gun-ports dropped, so as to cover the boards before fire was opened. These boards

also became a source of great trouble, as they were difficult to ship in the dark in bad weather and often got

badly warped. Other alterations for which we prepared were to have all the stanchions, including those of the bridge,

movable; we carried spare "dummy boats" which could be put in place or discarded. Spare ventilators,

or cowls, were also carried which could be shipped in various places. The top masts were telescopic, and we could

either be a stump-mast ship or a ship with a topmast. Spare yards and trestle trees were also carried, and could

be put up or taken down, likewise a crow's nest. The derricks could be stowed in different positions. A large number

of sansom-posts were carried which made the ship resemble very much a Blue Funnel steamer. Sidelight lighthouses

to be placed on the forecastle were another useful help in disguise, and these, together with other minor ones,

such as deck cargoes, rearrangement of life-belt racks, could be used either singly or in conjunction.

I have already mentioned how our aerial was an invisible one, but we also carried a visible aerial,

like any other, which could be put up when sailing neutral or occasionally as a British ship. This would be a disguise

that would be very noticeable, as whether the ship was fitted with wireless or not would invariably catch a seaman's

eye.

One of the best "dummies" we had was a large wooden "donkey-boiler funnel"

a funnel that is frequently seen in a ship either just before or just after the main funnel. In our ship the real

donkey funnel was inside the main one, so that our dummy one gave us three disguises: either we had none at all,

or else in front of the real funnel, or behind it. It was naturally a pretty heavy affair, and took some getting

"fixed." When not in use it was stowed along the boat deck.

I told one distinguished retired Admiral who commanded a Q sloop about our dummy donkey boiler

funnel, and he went one better. He had one made with a slit near the top and just big enough for a man to squeeze

inside. The funnel therefore served a double purpose, as in addition to disguise a man was kept inside as a "look-out,"

and he was, I believe, connected with the officer of the watch by a bit of wire attached to his finger, so that

as the officer walked up and down, the look-out got his finger pulled and couldn't go to sleep!

Another good disguise we had was to make the ship into a "flush-deck ship" In the plan

it will be seen that there is what is called a "well deck " between the bridge and the forecastle. But

by apparently building up the ship's side, which was done by stretching a bit of black canvas across tautly laced

to a wire, this well deck was filled in and the ship looked a straight deck the whole length. This disguise could

only be used in fine weather, owing to the canvas becoming shaky otherwise but when used it was a great boon to

the men, as it gave them an open-air recreation space. It had, however, its dangers, as one night when going into

harbour a tug came alongside and the pilot was just going to step on to what he thought was a deck. Had he done

so, he would have fallen some 10 feet. Without giving the show away, we told him that there was a brow ready for

him farther aft.

All the disguises and dummies I have mentioned were assumed in a comparatively short time, sometimes

an hour, sometimes a whole night. In addition to these more or less minor disguises we had ready a disguise of

a major order, to be used (as it eventually had to be) in the event of an unsuccessful action when we were certain

we had been seen. This disguise consisted of turning the vessel into a timber ship. We carried sufficient timber

to board up the ship the whole way round ; and this, together with a coat of light grey paint, stump masts, and

neutral colours, completely altered the class of ship. This disguise was also popular, as the timber was only outboard,

so we could do what we liked inside without being seen. We also carried a motor-boat on board, which was often

more trouble than it was worth, as it seldom "ran," and on one occasion caught on fire; but it came in

very useful for helping with disguises, as it could be stowed in different places, and we had a large crate, suitably

marked, made to cover it entirely if desired. Having now got the ship fitted up with everything we thought we wanted-though

we gradually found out we had forgotten many things and failed to foresee others, the next thing was to train and

rehearse for what we intended to do. This I will detail in another chapter.

CHAPTER IV

ORGANISATION AND TRAINING

WHILST the ship was fitting out one had to find time to study the ways and of the Mercantile

Marine, as everything, anyhow outwardly, had to be done in accordance with that practice. This meant not only receiving

long lessons from Lieutenants Beswick and Loveless, but also reading books and getting used to 'being quickly able

to refer to Lloyds Register and books of that sort. I arranged to be supplied with all the lists of sailings and

departure of merchant ships, so that when we wanted to accurately represent a certain ship, we had some idea where

she was. Organisation had also to be got ready for the crew. This included not only arranging for their accommodation,

but also for their stations in action and when cruising.

Although there was little difficulty in getting deck officers, I was seriously under-manned for

some time, being in two watches, there being only myself, Lieutenant Beswick, R.N.R., Lieutenant Jones, R.N.R.,

and an excellent young R.N.R. sub., Nisbet. The question of engineer officers was more difficult. I could have

kept ones in the ship, but they were unsuitable, owing either to age or other reasons. But I eventually unearthed

at the Naval Barracks an Engine-room Artificer R.N.R., who had been Second Engineer officer of the Loderer for

two years. I asked him to come, and got him demobilised and given a commission as Engineer Lieutenant R.N.R. -

rather a big jump, as it meant that from being a Chief petty Officer he suddenly became a commissioned officer;

but he more than justified my selection and eventually became Lieutenant Commander Loveless, D.S.O., D.S.C., R.N.V.R.

In order to carry out mercantile procedure, after seeing him at the Barracks I met him again at the Shipping Office

in the Barbican, Plymouth, both of us in " plain clothes," and signed him on as Chief Engineer, commonly

known as " Chief," and offering him certain wages which the Shipping Master agreed to, and I had Admiralty

authority to offer ; at the same time I signed on my Second and Third, Grant and Smith, both Scotchmen and worth

their weight in gold. I had not known them before, and they had been sent down from the Transport Department.

It is commonly believed that the crew were specially picked ; as a matter of fact they were drafted

in the ordinary way, and as the duty on which we were going was kept very secret, I think the drafting officer

thought the men were really going to an ordinary collier. I was certainly not impressed when I first saw my crew.

There were fifty-six of us all told ; this number was increased when I got the extra guns and some additional deck

officers, and, of the first lot, myself and the ship's steward assistant (who looked after the men's food) were

the only active-service naval persons, and I remained the only active-service naval officer throughout. I was lucky

in having as the senior rating a pensioner Chief Petty Officer, G. H. Truscott ; he had been Chief Boatswain's

Mate in some of the smartest ships of the Navy, and he became not only my Master-at-Arms and Chief Petty Officer,

but a most loyal friend. I don't know what I should have done without him, as he was equally loyal to Beswick,

and acted as a sort of go-between in the very difficult mixture of naval routine and discipline and tramp routine

and (?) discipline which we had to carry out. He was cut out for the job ; a bit of a martinet he may have appeared

to the crew at first, but he had great patience and tact in dealing with a very difficult and ignorant crew such

as we started with. The gunlayers (three) were R.F.R. men, the remainder a variety of R.N.R., fishermen, R.NV.R.-

in fact, a mixed crowd. One, for instance, was a market gardener, another a commercial traveller.

On going through them, I found that not a man had ever steered a ship in his life, though one

Irish-man told me he could steer well enough with a tiller. This looked rather serious, and I was on my way up

to the Barracks to see about it when I saw a man getting on in years sauntering about with a face like a seaboot,

and I casually asked him if he had ever steered a ship. He gave me a look I shall never forget, spat on the deck,

and asked me if I realised he had been Quarter-master in the Titanic, and was now " by rights " Chief

Quarter-master of the Olympic. (He didn't tell me his chief duty was probably looking after the ladies' deck chairs.)

I asked him if he would come on a " stunt." He came and remained with me till the end of the war, as

Quarter- master and my servant in mystery ships, and then as my coxswain in light cruisers.

Jack Orr was his name, and I have never met a more typical handy man. He was a brilliant helmsman

and an excellent servant ; the sort who puts your morning tea just out of reach, so that you either turn out and

get it or go without. Hairdressing, tattooing, and carpentering were among his other qualifications. I never once

saw him laugh during the three years he was with me. I tried hard to make him do so, but the most I could get was

a faint smile combined with an agonised face.

We commissioned on Trafalgar Day, 1915, and the first thing was to rig ourselves up for the part

; the Admiralty, not to be denied a chance of displaying their sense of humour, were graciously pleased to allow

each officer and man 30s. and 15s [15 shillings] respectively to " fit themselves out " with " plain

clothes." This was eventually increased to £3 and 30s. [£1,10 shillings]; and as we all not only

had to wear workaday " plain clothes," but also go ashore in them, the allowance can hardly be called

generous. Beswick and Truscott were deputed to get the outfit for the crew, and they would go ashore in plain clothes

either singly or together and get two suits and caps from some store and then leave them at a convenient pub to

be called for. The same sort of thing had to be done when we were at other ports, as it would have looked suspicious

if men had gone ashore in naval uniform to buy plain clothes in wartime. Most men brought private things of their

own from home to supplement the outfit.

This going ashore in " plain clothes " had its advantage as far as naval patrols and

restrictions for men in uniform were concerned ; yet, at one port to which we went, the men complained that the

girls wouldn't walk out with them because they were in " civies." One or two got attacked with white

feathers, so we got permission to wear the Dockyard badge in our buttonholes, which said " On War Service."

This led to a great deal of amusement at times. On one occasion, when at Pembroke, I was in my " get-up,"

had grown a moustache and no beard, and wearing my war service badge, which was commonly known as a " dockyard

matey's badge." My own cousin, who happened to be there, didn't recognise me, and being in uniform himself

was most indignant when I went up to shake hands with him and wanted to know who the -- I thought I was. My own

rig consisted of a reefer coat and a peak cap with a bit of gold lace wound round, and crossed flags in the centre.

The bit of gold lace round my cap was a piece of gold lace from uniform trousers which I hired from one of the

outfitters at Plymouth, on the plea of going to a fancy dress ball. Most of us grew beards or moustaches or both.

I rather fancied myself with a moustache and no beard. Anyhow, by the time we were all rigged up we looked our

part. Of course Beswick looked the best, as in addition to the fact that he lost his razor or didn't have time

to shave three days out of four, he had a thoroughly worn-out reefer coat with a patch in the back; and to make

him complete, the dog we had on board took a dislike to him and he had to find another patch for the scat of his

pants.

It can readily be realised that the duty on which we were going was one that would require ideal

discipline, as each officer and man would have a personal share in success or failure. Each man must not only know

his job but be relied on to do it without supervision and in the direst extremity. By reason of the very mixed

crowd with which we started, this question of discipline seemed difficult. I was practically the only one who had

been brought up to " strict Navy," and most of the others rather thought that discipline was only associated

with smart uniforms and spit-and-polish ; whilst now here we were all, officers and men alike, in dirty rigs, saluting

and other marks of respect being conspicuous by their absence.

In addition to this, the ship itself had always to look the "dirty old collier." Now,

it is well known that a dirty man-of-war is seldom if ever an efficient one, so this added to the difficulties,

which were overcome by realising that our upper deck and outer appearances were only part of our disguise, whereas

the living-spaces and gun-houses were our real selves and, therefore, clean. In fact, we combined an outward appearance

of slackness with an inner soul of strict discipline. We were fortunate in that we had no King's Regulations and

Admiralty instructions aboard to hamper us, and I was free to make my own regulations. We were only supplied with

such codes and signal books as were essential for secret communications. None of the usual Fleet Orders, etc.,

were issued to us, and I only ran across one flaw in this arrangement. We happened on one occasion to be coaling

at Devonport, about a year after we had been on the job, and I took the opportunity of sending Beswick up to the

office to look through the cordite list for destruction or return as having become dangerous. He returned with

the news that we had some on board that should have been destroyed some six months previous We therefore quietly

ditched it that night.

Obviously on the matter of discipline there would have to be a good deal of give and take, and

the mutual respect between officers and men necessary for good discipline and success must be earned, real, and

spontaneous. I found that having a common officers' mess helped a great deal. We were a very mixed crowd and brought

up under various different ways and thoughts. One fellow was a rabid Scottish Socialist, and we had many pleasant

hours arguing with him or playing chess, and many years after the war he admitted he was no longer a Socialist.

Another was the exact opposite and boasted much blue blood, was quite upset that he couldn't dress for dinner,

but nothing could stop him wearing his beautiful silk pyjamas!

We eventually became a very happy mess, but it was not too easy at first. Our first bone of contention

was of course the matter of how to feed. We appointed a mess caterer, and I suggested that our first meal aboard

at Plymouth - breakfast - should be a specially attractive one. It was certainly solid, but not attractive, as

I found myself faced at 7 a.m. .with a large plate of steak, onions, and potatoes! I suggested boiled eggs or a

bit of fish might be more suitable if obtainable and when in harbour : some agreed and some didn't; none of us

thought that the time was to come when we should be grateful for anything. Anyhow, steak versus fish for breakfast

became such an important matter, we asked Nisbett, as being our youngest member, to take on the catering, which

he did remarkably well for nearly two years: we messed well, and he had the tact to keep us all fully satisfied.

The best training-ground for seamen is at sea, and I early made up my mind that we should spend

as much time at sea and as little in harbour as possible. Since our hunting-ground was to be the Atlantic, the

season winter, and our ship an old one, older than I ever guessed, I knew that any "wasters " would soon