Wednesday, October 30. Priez-la-Fauche

Some days ago Schwab brought in a young officer to be interviewed. I have heard him stuttering around the hallway---stuttering both as to gait and as to voice. What history tells us about war concerns the mass movement of troops, and the victories, or otherwise, of this or that general in command. What meanwhile has happened to the individual foot soldier or his company officers rarely gets recorded. So here is one story at least. It has come out bit by bit in the course of several conversations---its fragments told in a most impersonal manner without a vestige of self-consciousness.

Captain B. of the 47th Infantry was admitted here September 11, 1918, with a sealed letter from B. H. No. 3 stating that from reports he was one of the best of the younger types of officers---brave and resourceful; also that he was blind when admitted to No. 3 and had very marked motor inhibition. Here for six weeks, with the diagnosis of "psychoneurosis in line of duty." He has improved steadily, but still stammers considerably and walks with a peculiar muscle-bound gait; has worked very hard to overcome this and is eager to get back to his regiment.

A clean-cut, fair-haired young fellow, 24 years of age, of medium height, and with the build of a football tackle. German parentage and exemplary habits---no tobacco or alcohol. Was very pro-German before the war, and in consequence has always felt that he had doubly to make good. In the Nat. Guard since 1911 and on the Border with the 1st Indiana troops. Enlisted in the Regular Army Jan. 1917 and was commissioned 2nd Lt. eight months later.

The Division sailed May 11, 1918, to Brest and May 19 to Calais. A lot of ill-feeling between our men and the Tommies---a British N.C.O. was killed---probably stupidity and lack of understanding on both sides. His regiment was billeted at Samer, some of the junior officers, three from each battalion, being sent to the British front for instruction. He saw a good deal of fighting during the Somme retreat and for nine days was constantly under fire---a very confusing time, with the British morale low. Felt terribly green, but tried to keep his eyes open and learn what he could.

Rejoined his regiment and was put in charge of a group of officers who were apportioned to our 2nd Division for experience. Was with them from June 5 to July 9, in the 23rd Infantry---Colonel Malone's outfit---under fire most of the time. Between June 6 and 10 came the taking of Bouresches and next the Belleau Wood affair by the Marines, supported by the 23rd. It was pointblank fighting, as hot as anything could be for a green man, and some places like Lucy were thick with dead. Still they got through, though the casualties were high; one battalion, for example, lost 75 per cent of its men when going through an exposed wheat field. Things were fairly quiet until July 1, when the 3rd Battalion of the 23rd and the 1st Battalion of the 9th took the village of Vaux---a very successful attack, but there were no reserves, and, had the enemy only known, they could have walked through.

Then a couple of quiet days, when the French on the right of the 9th Infantry went over, and, being a reserve liaison officer, he went with them---a fine advance, getting their objective, Hill 204, but they were driven back by a vigorous counter-attack, in which mêlée everyone had to take a hand with machine guns and rifles, observers and all. The French had to retreat even behind their former positions, with heavy losses.

On the ninth of July they were relieved by the 102nd (26th Division) and B. rejoined his own unit, the 47th, in reserve near La Ferté Milon, which the French were holding. It being supposedly a quiet sector, a lot of officers were loaned to the French for experience and observation. Here he learned what a real barrage might be, for between July 10 and 14 the enemy made a thrust at La Ferté, with heavy shelling. The French, about ready to quit, would only say, "Beaucoup de Boches---beaucoup de Boches." They dropped behind the barrage, while the attached Americans---company commanders, platoon leaders, and so forth ---went forward, got separated, and had heavy losses. Everyone was dumbfounded---some few French went forward with the Americans. In half an hour the French came back-pistol, rifle, and bayonet.

It was a brief episode, and after two days, he again rejoined his regiment, which had moved up to La Ferté. The 4th Division (the 58th, 59th, 39th, and 47th Regiments) had been stationed in a reserve line along the Ourcq from Crouy to Marchiel, and on the morning of July 14 the 39th and 58th attacked at Chézy, B. going with them, the 58th on the right so badly hit that the 59th leapfrogged them---an unsuccessful affair in which the 47th took no part. The next day the Boche offensive opened. B. was recalled to La Ferté and the division had no part in Foch's counter until the end of the first week. Meanwhile, being in charge of the wireless, he knew pretty much what was going on.

On July 25 or 26, he is not quite sure which, his regiment, being fresh and having had no part in the Chézy affair, was sent as shock troops---hustled in trucks through the other formations, first to bolster up the French at Grisolles and La Charme. From, there they were rushed forward where the advance had met its chief stumbling-block---Seringes, Sergy, and Cierges. They were all night in going up, made their way through the Forêt de Fère, which was full of gas, and to the open fields beyond. Here the 42nd was holding the line, the Alabamans (167th) to the left and the Iowans (168th) to the right. The 47th was to go in between them toward Seringes and Sergy, but being then only a lieutenant he knew nothing of the plan.

They were just too late in getting through the woods to follow the barrage which had been put up for the attack, and had to go it unprotected in double time to catch up to the 168th and 167th, who had already moved forward. No sooner had they emerged into the open than they met a heavy fire. The lieutenant colonel and one major were severely wounded, and soon the other major and B.'s captain were killed, leaving him senior officer of his battalion.

About this time a general appeared from somewhere and asked B. if he had received any orders, which he hadn't, and with a wave of his arm the general said, "You're to cross a river over there and take a town called Sergy." It was tough work---the men had marched all night---they formed. combat groups and went through wheat waist-high under direct fire from the Boche artillery. They carried one day's rations, one hundred rounds of rifle and one bag of chochant (automatic) ammunition. In some unaccountable way, Company L had received an order to withdraw, leaving what remained of three full companies, circa 700 men. The Ourcq, which proved to be a mere creek, was crossed with a run and jump, and, getting into Sergy, they fought their way through by 10 a.m., finally being brought to a halt beyond the village at a sunken road which was filled with machine gunners.

There was terrific shellfire, both our own and the enemy's, which seemed to be concentrated on Sergy, and finally, after heavy casualties, they had to fall back as far as the Ourcq again. Here they established not only their battalion P.C., but a first-aid station in a battered mill (La Grange au Pont), and did what they could for such of their wounded as they could drag in. Later in the day, after heavy artillery firing, the enemy countered. The dwindling battalion met them in the village and drove them out as far as the road again. The Boches came back with reënforcements, and all night there was house-to-house fighting in the village---the boys standing it very well despite their fatigue and losses.

On the next day, with no artillery aid, they succeeded in getting the village again cleared back to the road and held the Boches there till dark. Then the Boches countered once more and drove them back to the mill, where they again held and spent the whole night in once more clearing the village, which they succeeded in doing by dawn. That day the Boches came back at noon and reached the mill---and so it went, back and forth, the place changing hands nine times between Friday the twenty-sixth and Tuesday the thirtieth, the twenty-eighth being their worst day. They finally held at the road on the thirtieth and were relieved on Wednesday the first.

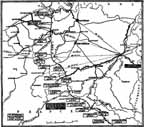

Contours of Allied Advance from the Marne to the Vesle, July 19 to August 14. Note Bulge at Fère-en-Tardenois, Sergy, and Cierges, where the Advance Was Long Stalled during the Last Week of July owing to Severe Enemy Attacks Which Covered His Lines of Communication and Permitted His Final Withdrawal

Practically without sleep, with no medical officer, with only such food, after the first day, as they could get off the dead, with almost incessant shelling and many hours of actual combat every day, it was something of a strain. On Tuesday night B. got over to the 168th, and the colonel wanted an estimate of his strength in view of a possible widespread attack: "18 men and one officer fit for duty"---out of 927 men and 23 officers, these alone were left.

B. admits that he was getting rather fed up. He was acting as gas officer, for many of the men were suffering from bad burns and all had been more or less gassed. Then as intelligence officer---in other words, as a runner, once or twice by day and two or three times by night, always in the open---a necessity, since lines that he got over to the 168th were soon blown to bits and there was no one at the 168th P.C. who could read flash messages; there was no communication at any time with the rear. Also as medical officer, directing the getting in of the wounded, always under fire, back to the mill; he did two leg amputations himself with a mess-kit knife and an old saw found in the mill. One night they had sent back 83 wounded men on improvised litters.

When sufficiently quiet, the nights had to be spent in searching their own and the enemy's dead for food and ammunition. They once got down to as low as twenty rounds of cartridges, and much of the time they used Boche rifles and ammunition---also Boche "potato-masher" hand grenades, which caused at first a good many casualties among the men, for they were timed at three or four seconds instead of four or five like ours. The Boche food was good when they could find it---sausages and bread and Argentine "bully."

The least fatigued men had to be used to get in the wounded, for it was an exhausting process, since they often had to be dragged along a foot or two at a time, as occasion offered. Many men with three or four wounds continued in the fight---had to, in fact---and a sound man and a wounded man often fought together, the latter loading an extra gun even when he might not be able to stand. Their only protection was to get in shell holes.

During these days B. saw for the first time a case of shell shock, though he did not know what was the matter with the man---thought he was yellow. Every time a shell would land near, he would race to shelter, shaking and trembling; but he always came back and got to work. He simply couldn't stand the explosions. They were all pretty shaky from the almost constant artillery fire---high explosive alternating with gas of one kind or another. Many of the men still fighting had mustard burns.

But almost the worst was a "rotten-pear" gas which made them sneeze and often vomit in their masks, so they had to throw them away and take a chance. Everyone was more or less affected, and marksmanship was poor from lachrymation.

On Monday, B. was quite badly stunned by a high-explosive fragment which struck his helmet---like getting hit in the temple by a pitched baseball. Men often thought they were wounded---would feel a blow on the leg, perhaps, and see blood and a tear, but on slipping off their trousers would find only a bruise, the blood having come from a neighbor's wound.

On Tuesday afternoon the Boches sent over a terrific barrage---a combination of artillery and machine-gun fire. They had learned by this time that after a barrage the only thing to do was "to beat the Boches to it"---so he and Lieutenant K. with their eighteen men rushed them (there were some two hundred Boches) and succeeded, after a sharp engagement, in getting into their positions along the sunken road just north of the village. It was a case of "Gott mit uns," for not one of the eighteen was killed. They captured some machine guns, and, getting them in favorable positions, held the enemy off.

Not long after, word came by runner from the 168th to hold on, for they were soon to be relieved. B. sent back word that they couldn't hold much longer without reënforcements, and fifty men were sent over from the 168th in support. At about 2 a.m., B. and two men with chochants and grenades crawled out and put out of commission an Austrian 88 which had been trained on them and from which they had suffered much. They captured the crew and officers. It was the last post holding the sector. The Boches had evidently begun to withdraw.

About this time Seringes was taken by the 1st Battalion of the 47th on their left. They had probably gone through similar experiences, but apparently Sergy had been the most difficult nut to crack. Cierges had not yet fallen.

Wednesday, a day of intermittent firing, was spent in collecting the wounded. They were relieved at sundown---two officers and eighteen men---and they marched all night to get back, all very much done in. Lieutenant K. had been hit through the heel---was cursing and swearing, and quite out of his head. The men all appeared low indeed---one chap, Madden by name, had had no sleep the whole time, for he had been acting as runner on the left, three or four times every day under observation and fire.

They went through the Forêt de Fère and met the chow wagons about noon---found a new acting-colonel who knew precisely what to do; gave the men good food and made them go to sleep. Not until they had arrived did B. notice that he was shy of his tunic, in the pocket of which was his artillery code---had left it under the head of one of the men, who was badly hurt, and forgot it when the time came for them to go out. Insisted on going back after having a rest---was afraid someone would find it. Was given a motor cycle and to his great relief found the coat where he had put it, but the man was dead.

On coming out he saw one of his own men who had been wounded and was overlooked near the mill at the far edge of the creek. He went down and tried to get him across the creek to the motor cycle, but the Boches opened up and they could not duck fast enough. B. felt a heavy blow on the top of his helmet, which mashed it in against the back of his head. He fell forward---had a sick feeling-found he was bleeding from the mouth and nose, and the back of his neck was bloody. Started to look for the man and found him all cut up with a huge hole in his side and a glassy stare, so he knew he was a goner and left him---reached the cycle and started off under heavy fire.

As soon as he got back they saw something was the matter and gave him a stiff drink of whiskey---he tried to sit down, but came down heavily with a jar, and began to shake and stammer. He was afraid to go to sleep---had an idea he would be unable to see when he woke up. They threw cold water on him, and he felt that his entire left side had given way and all vision was gone except a yellow fog in front of him. Through all this he still had a feeling that he was O.K.---merely exhausted and needed sleep. He was very sick, vomiting more or less all the rest of the day--ears humming---everything swimming.

They wanted him to go to a hospital, but he remembers fighting them much as a football player sometimes does when he is forced to leave the field after an injury; has strangely vivid memories of this occurrence and subsequent events---patchy, though very acute memory pictures. Knew by the hum of the machine that it was a G.M.C. ambulance; couldn't see much except a yellow cloud before his eyes; was taken to a field hospital and a doctor asked him what was the matter. He said "Nothing," he merely wanted a little rest; was talking well enough at the time.

First in a horse-drawn wagon, then in a Ford ambulance, a very rough ride, to No. 7 at Coulommiers, a matter of a good many hours---does not know whether he was alone or not. Terrific headache all the time. His hearing was getting bad---a constant hum in his right ear. When the machine would scrape branches of trees it sounded to him like the whish of a shell---the worst sounds he had ever heard. .

"Of course if they had known we were so weak they could have come through at any time. You see, I am now Senior Company Commander and I want to get back because I can have the pick of the companies and can get into some really big push before it's all over.

"The chief trouble now is the dreams---not exactly dreams, either, but right in the middle of an ordinary conversation the face of a Boche that I have bayoneted, with its horrible gurgle and grimace, comes sharply into view, or I see the man whose head one of our boys took off by a blow on the back of his neck with a, bolo knife and the blood spurted high in the air before the body fell. And the horrible smells! You know I can hardly see meat come on the table, and the butcher's shop just under our window here is terribly distressing, but I'm trying every day to get more used to it. Yes, it was unpleasant amputating those men's legs, and we had to sharpen a knife from a man's kit for it, but what could one do otherwise? It was not quite so bad as dragging the wounded men in, hunching along foot by foot, both of us on our backs and under direct fire all the time---that was interminable. But the worst of all are the dying faces that come to me of the men of the command---the men I could not bear to see die---men whose letters I had censored, so I knew all about them and their homes and worries and dependents.".

Thursday, Oct. 31st

A "guest" here, a fortnight now---unfortunately missing the last act of the drama. It's a curious business---unquestionably still progressing---purely a sensory affair, fortunately without pain, though with considerable muscular wasting. The paresthesias are chiefly in soles and palms and I have a vague sense of familiarity with the sensation---as though I had met it somewhere in a dream. Like stepping barefoot on a very stiff and prickly doormat---a feeling, too, as though the plantar and palmar fascias had shrunk in the wash and were drawn taut. As Gowers used to say, our sensations transcend our vocabularies. But it's so characteristic someone who has it ought to describe it---preferably a doctor.

Such a one, however, has himself under observation---the fool for a patient idea---well, it doesn't work very well and that's possibly why---though there have been exceptions, like Bernhardt and his meralgia---why M.D.'s as a rule don't scrutinize their own maladies too closely or describe them. They traditionally wind up with what they have been chiefly interested in---the examples are many. Accordingly I should properly be in hospital with G.S.W. skull" rather than with this. It would have been appropriate and more interesting to watch.

The Conférence Interalliée has again assembled in Paris. There have been 4482 deaths from influenza among the civil population of England the past week.

Friday, Nov. 1st

All Saints' Day, and Hallowe'en was celebrated here last evening by a dance for the enlisted men of the Unit and the patients---very festive, I'm told by the nurses of my floor. The men, who had spent the day digging the hobnails out of their shoes, are probably far better dancers than the officers, to whom heretofore the privilege of dancing with the nurses has been restricted.

The news astonishes. Old World dynasties are tottering, and the Kaiser stands a lone figure in the democratic ferment which is beginning to affect even Germany. L'ARMISTICE EST SIGNÉ AVEC LA TURQUIE!! is heavily headlined in Le Petit Parisien which reaches us late in the evening. Among its conditions are the right of passage of the Straits---the occupation of the Dardanelles forts---the immediate repatriation of prisoners. Nothing equal to this since the dégringolade of Bulgaria.

Sat., Nov. 2nd

During the past few days the Austrian Army has become little more than a demoralized rabble; and yesterday the Allies opened up again against all the vital points from the Dutch frontier to the Meuse. The Turkish terms are published and Austria will be able to judge what her own may be.

Sunday, Nov. 3

a.m. My hands now have caught up with my feet---so numb and clumsy that shaving's a danger and buttoning laborious. When the periphery is thus affected the brain too is benumbed and awkward.

Still, there are bright spots. A visit from Kerr this morning with documents from the office---also McLean, with a new novel and the news. This grows more and more amazing every day--the collapse one by one of the props on which Germany has built up her dreams of world domination---Mittel-Europa and the East.

p.m. For the first time since Wednesday from my chair laboriously to one of our Dodge cars. Soft air---soft smoky colors---the foliage almost more beautiful than in its earlier stages of ripening. As far as Reynel and back---the old peasants in their white caps---church bells ringing---even the cows idled about the villages with the air of permissionnaires, as though taking a deserved Sunday afternoon off. The French gardener here is planting pansies along the south wall of the L----- "so the Americans can send blossoms home in envelopes to their sweethearts."

Monday, Nov. 4th

The Kaiser's abdication is again officially announced as imminent, and after a statement that he approves of the constitutional amendments he betakes himself to the German H.Q. for the protection of his troops. This via Zurich. The King of Bulgaria has started the abdication fashion.

Since July 15th the Allies have taken 362,355 prisoners. There is a cry in England for a Ministry of Health, and Sir Auckland Geddes tells some "appalling facts about the health of the British nation." The pandemic of influenza may after all have served a worthy purpose. It takes a scourge---or a war which is but a scourge---to rouse nations to constructive acts.

Nancy dedicates a monument at Barthelemont to "the first three American soldiers to give their lives to France during the present war." They were killed on November 3rd, 1917. There are some American noncombatant graves of Sept. 5th among the forest of crosses at Étaples which seemingly are forgotten.

Wed., Nov. 6

It was a year ago to-day that the last desperate attack was made by the British for a few yards more toward Passchendaele, leaving a British Army discouraged and decimated after three months of desperate fighting with gains so slight it was not even necessary to move the hospitals forward. To-day what a different story and what a different type of warfare, with an enemy being pursued at all points despite his rear-guard machine-gun nests!

The Americans have made their way across the Meuse, threatening the pivot of the enemy's retreat. The Austrian terms are made public. The Hun is at bay---Russia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Austria, one by one have abandoned him, and now the Bavarians, their southern border exposed, grow restless and threaten to follow suit.

Nov. 7th, Thursday

M. Clemenceau in a "vibrante allocution"---one can see him---makes known to the Chambre the terms of the Austrian armistice whereby she is stripped of her army, navy, and the territory she has invaded. Day by day the victorious Allies sweep on with an ever-shortening front, as one can even appreciate in hospital, unable to follow the receding line except on an official map with pins and a ball of yarn. My only form of amusement; but I 'm no longer able to hold and stick in the pins.

The British on one side of the Ardennes have gone through the Forest of Mormal and progressed along the Sambre toward Maubeuge and Mons. On the other side, the Americans have finally broken through in the direction of Stenay on the Mézières-Metz line. In between these pincers the Boche forces may become trapped, and a second Sedan be the result unless mayhap they can manage to trek through the forest, for they are clever at extricating themselves.

But these occurrences are outside of Germany. Inside, things also are happening---most significant of all an amazing "proclamation to the people" from a New Government, concerning the transfer of essential rights from the Emperor to their representatives---freedom of the press and the right of meeting. "Le Gouvernement et, avec lui, les chefs de l'armée et de la marine veulent la paix: ils la veulent loyalement, ils la veulent bientôt." This unquestionably is to prepare the German people for the terms of an armistice which cannot possibly be any less rigid than those imposed upon and accepted by Austria and Turkey. Mr. Wilson's note of yesterday---probably to be his last---says, "Ask Foch"; and it is stated that a delegation left Berlin instanter for the Western Front for this purpose. But why a delegation and not an officer with a white flag?

It hardly seems possible that these are the same people who a short fourteen weeks ago were sweeping victoriously toward Paris and Amiens and the Channel Ports. Nor the same people Mc-Carthy has just been telling me about---the Berliners of 1916. He was serving with Alonzo Taylor in the Embassy under Gerard at the time, with the unpleasant duty of inspecting prison camps, and was asked on one occasion to go to a meeting of Army medical officers---an invitation he accepted. At the opening of the meeting the assemblage arose and at a signal raised their right hands, roaring in unison, "Gott strafe England." With this benediction they resumed their seats and proceeded with their business. McCarthy, having an Irish sense of humor, had great difficulty in concealing his emotions for they were, to say the least, considerably mixed. He has been here for several days on a visit and his experiences in the Diplomatic Service would make a book. He was more or less mixed up in the Casement affair---in the Fryatt episode, which he fears he precipitated by his search for the four women prisoners. In the officers' prison camps he had many strange encounters, such as the meeting with Christian Denker, late of the J.H.H. and Hull House, Chicago, a prisoner at Maidenhead complaining that they were badly treated by not being given the daily papers from the Vaterland; and, what's more, the roof leaked!

All of our Embassy people, though they were carefully watched, had laissez-passer's which gave them freedom of movement and certain powers of inspection---one in particular which they called the "Weer Willy" owing to its Wir Wilhelm beginning.

Crile here for the day visiting the hospital and Thayer in for a moment after dinner. To our relief he is able to contradict the depressing rumor to which we had endeavored to adjust ourselves, namely, that Woodrow Wilson has been assassinated. Thayer is off for England with Longcope. To-day almost my worst day so far---the labor of dressing too much for me.

Friday, Nov. 8th

My room is changed so that Schwab is no longer afflicted by having to adjust his habits to those of a semi-invalid. With such trifles to emphasize the days, they slip by.

Alec Lambert in at noon. He shares my tray and between the killing of flies makes toast over my wee fire. He brings the news that Foch has notified the German envoys to proceed along the Hirson-La Capelle road to our outposts.

The American advance yesterday with our successful crossing of the Meuse will probably help them to accept the Allies' terms, whatever they may be. After our long steady pressure we have finally burst through to Sedan, and when the story comes to be told it should be a thrilling one. The old home of the de la Marcks and the de la Tour d'Auvergnes, where Turenne was born, which Vauban fortified, where Prussia within living memory struck the most crushing of the blows which laid France at her feet, delivered of its Boche invaders by a despised army of Republicans from beyond the seas---Prussian militarism defeated on the scene of its most brilliant achievement in that war which made Militarism the popular ideal---it is the finger of fate!

Later. Foch, after an interesting exchange of radio telegrams, received the German plenipotentiaries this morning---they had crossed the lines at Haudroy last night.

The armies are pegging away to the last---the Americans have entered Sedan and cut the railroad connecting the important towns behind the enemy's present front. The British are within eight miles of Mons. There is a revolt under the red flag in Hamburg, another at Kiel, and popular outbreaks are reported at Cologne. Messrs. Erzberger and Oberndorf, Generals von Gündell and von Winterfeldt, may well hasten.

Nov. 9th. Saturday

We have received the news of a possible armistice with a peculiar indifference almost amounting to stupefaction. No shouts or throwing up of hats---we cannot believe it quite yet.

Finney and Salmon in to see me this afternoon. F. still under the weather with his particular kind of grippe. Salmon knocks into a cocked hat my plans to keep on at work here and to organize the nucleus of a National Institute of Neurology in the A.E.F. at Vichy. The war's over---people are tired, God knows---the Army (especially McCaw) will not listen to any new constructive schemes---sick and wounded will be shoved home immediately at the rate of 10,000 a week---America will be much more receptive to such an idea, and an institution transplanted from the A.E.F. won't "take"---first thing necessary is to beat it home and get a gigantic triage started at the Staten Island plant where cases can be combed out, sorted, and routed to proper hospitals---for this purpose should have representatives there of all departments, and Schwab, McCarthy, and I are suggested for Neurology.

Salmon is the only man who can put across such a large scheme. Will he be willing to go and do it? He favors a university rather than Red Cross or national auspices for the proposed Institute---possibly with the General Education Board's backing. Above all, avoid any relations with Congress, for if it has any brains it doesn't use them---"a Congressman is nothing but a heart and a pants pocket"---just sentiment and cash, in other words.

The German delegates were belated in getting over the roads Thursday. Whereas Foch ordered a cessation of firing at 3 p.m. to permit their passage, they did not reach Guise until late that night. They stayed at the château of the Marquis de l'Aigle near the Forêt de Compiègne, and apparently were admitted to Foch yesterday morning. He received them in his train at the Rethondes station and gave them 72 hours to reply---i.e., until Monday at 11 a.m. There will probably be tearing of hair at Spa, the Grosse Hauptquartier, "mais la situation militaire et la situation intérieure parlent un langage singulièrement impérieux."

The Wittelsbachs after 800 years of rule have been dethroned and a republic has been proclaimed in Bavaria---the Socialist Party has given an ultimatum demanding the abdication of the Kaiser and renunciation of the Crown Prince---the German fleet at Kiel has mutinied---the French approach Hirson and the British are drawing near Mons.

Nov. 10th

Max of Baden dismounts as Chancellor and Friedrich Ebert, a saddler, is in the saddle. The Kaiser, after doubts and hesitations, is finally reported to have signed his abdication last night at the German headquarters in the presence of the Crown Prince and Hindenburg. L'incroyable est accompli. There is much talk of what Wilson really means by "the freedom of the seas" among his 14 covenants; and the story is circulating that there was a good deal of difficulty at the Versailles Conference in fully understanding other of the Fourteen Points. Finally Clemenceau in some desperation said, "Why, the Bon Dieu has given us only ten."

Later. It is told that the German envoys on being admitted to Foch asked for an immediate provisional cessation of hostilities "on the grounds of humanity." This was rejected by Foch. The story I have heard through General Glenn is that von Winterfeldt breezed into the compartment with a sort of old-chap-how-are-you air and that Foch looked him in the eye with no sign of recognition. Also that the first demand was not from them but from Foch, for the secret plans for all the traps and delayed mines placed under bridges and in towns in the line of the retreat. It was through this that Ostend was saved. Von W. had been military attaché in Paris at the time of the 1913 manoeuvres and was given the Légion d'Honneur. I wonder if he wore it last Friday.

Nov. 11th. Monday

La dynastie des Hohenzollerns a été balayée; but in this process some twenty millions of human beings have perished or been mutilated, and who is to be held responsible for this? The terms of the armistice were signed early this morning, though the signal to "cease fire" was not given until the 72 hours were up, viz., at 11 a.m. In these last few hours many poor fellows must have needlessly fallen.

Thus the Great War ends at the eleventh hour on this eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918; and the Kaiser awakes from his forty years' dream of world dominion. It's a piteous spectacle. All the king's horses and all the king's men couldn't put Humpty Dumpty together again. He came so very near to fulfilling his ambition---the Hohenzollern rule of a Prussianized world. Weltmacht oder Niedergang. He gambled and lost, so it is to be downfall.

The past few days have been comparable to the last few minutes of a decisive intercollegiate football game at the end of a season. On one side of the field, alive with color and excitement, an exultant crowd, touched by the last rays of a November sun---an unexpected victory within their grasp through an unlooked-for collapse of the visiting team. Across, on the other side of the darkening field, tense, colorless, shivering, and still, sit the defeated, watching their opponents roll up goal after goal as they smash through an ever-weakening line that shortly before seemed impregnable.

Just so, till the whistle blew, the Allies plunged ahead on the five-yard line of the Western Front. The Americans pushed over at Sedan---a mass play carried the French beyond the Mézières-Hirson line---and the British Guards Division on the left centre went through to Mauberge and Mons, where early in the game they so desperately and hopelessly resisted an apparently unconquerable foe. Surely the Bowmen of Agincourt, the Angel of Mons, and Saint George himself must have appeared yesterday, even as they are said to have appeared in those tragic days of August 1914.

It's a trivial comparison,---a world war and a football game---but when something is so colossal as to transcend comprehension one must reduce it to the simple terms of familiar things.

Kerr and Bagley here in the afternoon to discuss plans for a survey of the peripheral nerve cases and the ways and means of keeping track of them. Later Pte. Duncan brings me from Neufchâteau a much needed shaving mirror and nail brush. He takes back with him my tunic for alterations---chickens on the shoulders and three service stripes on the left sleeve. Almost too much for one day---the completion of 18 months since our embarkation on May 11, 1917; a colonelcy; the cessation of hostilities.

How still it must be with the guns silent---they can sleep now "amid the crosses row on row." There will be much celebrating, I presume, and drawing of corks---but perhaps not so much after all. That would have happened after the football game---a large dinner and the theatre---wine and song. This contest has been too appalling for that kind of thing, and there's a lot yet for everyone to do. . . .

We celebrated simply here before a wood fire with tea at 4.30---the Matron, the Padre, Schwab, and I---and after wondering what the future held in store for us we switched to a serious discussion of religion which was prolonged till dinner time. The Padre admits that Army chaplains have learned much in this war---especially about men. For example: a trench-going Padre makes a church-going battalion. He thinks he will no longer wear clerical garb when he gets home---and he lingered to say that though the Jew was an agnostic he thought him one of the most religious men he ever knew. Wethered said something like this about Capt. Telfer at No. 46 C.C.S. last summer.

Tuesday, Nov. 12th

What an opportunity to redeem himself before his people by facing the music the Kaiser missed, and how ignominious his flight! So far as one can gather from the fragmentary reports, it was before the terms of the armistice reached Spa. The German courier, leaving the French G.Q.G. near Senlis after many vicissitudes, was reported by wireless to have reached the German Headquarters at 10.55 Sunday morning. A message from The Hague states that the ex-Emperor arrived Sunday morning by special train at the Eysden station on the Dutch frontier. He is reported to have signed his letter of abdication Saturday night.

Wednesday morning, Nov. 13th

On ne se bat plus. It's an intoxicating November day which must reflect the gayety, light-heartedness, and thanksgiving of France. What must Paris be like---the boulevards crowded---the Strasbourg statue, after near 50 years of mourning, probably bedecked with banners and flowers---the Place filled with captured guns---the blue glass all removed from the street lamps---what would one not give to be there!

It's blowing here and the last yellow leaves from the poplars are joyously zooming and side-slipping and nose-spinning as they leave their hangars and seek somewhere a safe landing place. The leaves indeed are mostly gone, and the fruit trees which I can see from my windows, crucified against the walls of these old farm buildings, are quite naked---only to the chestnuts do leaves still cling, and to some of the lower branches of the beeches unswept by the wind. It blows down my chimney too and sends gusts of wood smoke into the room, and my morning toast made on a pair of tongs smacked of it.

The sun was pouring in when my batman appeared, started the fire, stropped my razor (for that particular gesture is beyond me these ataxic days), and brought my green canvas tub---the very tub that one "Chopsticks" scrounged for me in Lillers, eons ago, and now it in turn begins to leak, a lamentable circumstance, for the like of it comes not with the A.E.F. Then bacon and the smoky toast and a pot of G.W. coffee with the aid of my old friend "Beatrice," faithful since 46 C.C.S. days---and now in bed again enveloped in a blue-gray dressing gown which harks back to Geoffrey Dodge and my first trip to Paris near 18 months ago. La guerre est finie, and what a procession of associations these familiar objects serve to recall. It's doubtless why we cling to old things---old books, old friends---an ancient pair of slippers, no matter how shabby, may be rich in memories forever lost on replacement with what is new---and clean.

Thursday the 14th

Another brilliant morning. In the farm courtyard below chanticleer crows, guineas and geese cackle, porcs grunt, and the beagles bark excitedly. Frenchmen of the vintage of 1870 in their velveteens are doubtless making for the bois to get a pot at a wild boar or two. The Boches having now been finished by the younger generation, there is ammunition a-plenty for them and the boars. .

A last ride this afternoon, taken early, for the sun lies low and cold by three. Through the forest roads again, with a climax on a hilltop overlooking the valley, the horizontal rays of the sun streaming through an open wood of towering silver birches with spruce and hemlock for a background. The leaves nearly all wind-blown by now except the lower branches of oaks and beech, though from a distance one can still recognize the patches of birch, clearly demarcated from the rest of the forest by their striking color of burnt sugar.

Friday the 15th

Yesterday afternoon for the first time well enough to attend the Reclassification Board Meeting---very interesting---conducted like a hospital clinic, each M.O. presenting his own cases for "boarding," with diagnosis and class in which he believed the patient should fall---then, after the man was dismissed, a free discussion. The presentations admirably made by young M.O.'s like Durkin, Thorn, Clymer, and others. Schwab deserves unending credit for the way in which he has built up this school of unconscious instruction and made an interesting daily seminar out of what in most places is regarded as a chore.

All the advantages of a full-time university service---paid by. the government---no outside responsibilities---no office hours to keep---merely undivided attention to the work at hand, and the work made interesting and vitalized by the thought that perhaps to-morrow any individual may have to stand on his own feet as psychiatrist to a division or regiment. There is nothing quite like this combination in civil life---no comparable incentive. How can we transfer some of its good features to civil conditions?

Saturday, November 16th,

7 p.m. Adieu, La Fauche. Four weeks there were somehow passed, under the kind attention of Schwab and his people. So in the old Dodge back to the attic of 57 rue Gohier in Neufchâteau, with its smells and draughts and flapping paper partitions. We huddle about a cylindrical iron stove and envy the deaf Duncan, the mangy "Gamin," and the slatternly Henriette, who together occupy the warm box of a kitchen. Too tired, squalid, and uncomfortable to talk to one another, we scarcely need to do so while familiar shibboleths resound in our ears---that this was to be a war to end all wars, and that the world from now will be made safe for democracy. We wonder. We shall at least see what democracy can make of it---and after all this destruction there is certainly much remaking to be done.

And these shall be no easy idle years,

For only by the toil of stubborn men,

Of women toiling stubbornly with men,

Shall earth attain her heritage of dreams.