James Mechem |

![[Photograph: Author James Mechem

in New York City the day before his 80th birthday, Oct. 30, 2003.

Copyright 2003, Denise Low]](jamesmechem.jpg) Author and magazine publisher James Mechem in New York City the day before his 80th birthday, Oct. 30, 2003. Copyright 2003, Denise Low. |

Denise Low: I've known you since 1980. I remember hearing you read a short fiction piece at the Salina reading for the Kansas Writers Association.

James Mechem: I still have a Kansas Writers Association tee shirt.

DL: That was my first Kansas Writers Association meeting. I can't even remember how I got to it. Maybe Tom Averill got me involved with it. I remember the first time I heard you give a reading, with your soft-whiskey, gentle voice, about lesbian lovers, I believe. I was so taken with your presence, and then the story was so distinct. It's a lot like the stories you publish now in Caprice. Did you grow up in Wichita, where you lived?

JM: I grew up in Topeka. I was born in Wichita. But when I was six years old we moved to Topeka, and I didn't come back to Wichita until I got married.

DL: What did your father do?

JM: He was secretary of the Kansas State Historical Society. They called him the State Historian.

DL: Did that have an influence on you?

JM: I don't know that it did. He was the one who told me I should be a writer. After I got out of high school, he wanted me to write for a year. He gave me a little office in the building that the historical society was in. Kansas Teachers' Magazine had been having him write a magazine article every month, nine months a year. He had been writing an article on history every month. So he had me write a year's worth of articles, because all the research was in that building and all the librarians were at my command since I was his son. I didn't have to research at all. They gave me all the stuff and I gave them nine different subjects I could write about, and I wrote the articles. But when they were published, they didn't sound too much like me.

DL: So he edited them?

JM: Yes. They came out under his name. I ghost wrote them.

DL: What year would that be?

JM: Let's see. I got married in 1950. And I came home from the wars in 1946. This wasn't after high school, it was after the wars, so 1947 or 1948

DL: What branch of the service were you in?

JM: I was in the army medical corps. My name was Medic. That is what I was known as.

![[Photograph: Author Denise Low, Lawrence, KS,

in New York City, Oct. 30, 2003. Photograph by James Mechem]](deniselow.jpg) Lawrence author Denise Low in New York City, Oct. 30, 2003. Photograph by James Mechem, used on cover of Caprice magazine, Vol. 19. No. 1, Winter 2004. |

DL: Did you go to college after the war?

JM: Oh, yes. I applied for St. John's College in Annapolis. They had an experimental program there. I thought it was a good deal. But then my father, he could talk me into anything. He talked me into going to the University of Iowa because they had a good writing program. Paul Engle was there and other people were there. But when I went to the University of Iowa, instead of taking literature, I think in the spring semester I took magazine writing. That was awful good. But a better college for me, my father said, is the University of Oklahoma. He said, they don't guarantee you a degree, if you take the writing program, but they will get you published. So he talked me into transferring to Oklahoma. So I went to Oklahoma. I didn't get a degree, but I did get published, in 10 Story Western,, with my name on the cover. Forty dollars I got for it.

DL: What was your dad's name?

JM: Kirke Mechem. My brother's name was Kirke Mechem and my son's name is Kirke.

DL: Was your dad born in Kansas?

JM: Mankato, Kansas, in the 1890s I think.

DL: That goes back a few years. It strikes me as unusual that a man of that time would want his son to be a writer.

JM: He wanted to be a writer himself. Doubleday published his only novel. It was in a crime series. It was called Frame for Murder. That wasn't his title, but that was their title. Well, he wanted to be a writer. But mainly he wanted to be a playwright. He wrote in verse. He won several national awards for it and gave readings as part of the prize. And then also the little theater in Topeka, he would work with them and write plays and they would produce them. He wrote a lot of comedies. And he would make us kids read them. I read so many plays when I was a kid that now I can spot a movie that was based on a play, and I don't like them.

My dad wrote a play called John Brown, based on, of course, history, which he knew well. It was verse drama, and it won the Maxwell Anderson Award, which they gave annually to the best verse drama. My brother writes operas. He wanted to write an opera about John Brown. My father was still alive when my brother got this idea. But they had so many fights over it that my brother had to quit working on the opera until my father died. Then he finished it.

DL: So you came back from the war and spent a year working with your dad in the state historical society. You went to college. You met your wife.

JM: Yes. My wife and I decided we would get married but my dad talked me into going to Oklahoma. That wasn't in her agenda. She went to Iowa because they had a good school for physics and chemistry. You've heard of Enrico Fermi? He was teaching there, and his daughter was there too. So they had a good science school. And it was the best school in the country for stutterers. And she stuttered. That's where she wanted to be. She wanted to be a doctor.

Anyway, she decided that she would stay in Topeka while I went to Oklahoma and she would work in a laboratory making money. I was on the GI Bill of course. Then we could get married after a year. And so we did and got married and went to Oklahoma. She worked in a hospital there in Oklahoma. Neither of us graduated from Oklahoma. We moved back to Wichita and went to work for Boeing.

DL: You were a technical writer for Boeing?

JM: At first they put me down in the shop to do hydraulic parts. Then they had over the radio that they wanted writers for training manuals, and so I applied for that, and they said okay, but you're going to have to take a test. I said, why don't I write you a story? I sat down for an hour and wrote them a story, a fiction story. I had been writing pulp fiction all along. And they accepted that as me being able to write, and so they put me in the training department writing training manuals. And that may be why there are so many airplane crashes today.

DL: So had you been publishing your pulp fiction?

JM: Yes, I was working at Boeing when my magazine story came out with my name on it, 10 Story Western and I showed it all around. I think I was still in the factory, and that's one of the reasons why when I applied for the training and they asked the people I had just been working with, what they told them was I was a writer. I wasn't writing pulp fiction at Iowa, I was writing literary fiction. It's hard to write literary fiction. And nobody likes it anyway. They just give prizes to it. Nobody gives prizes to pulp fiction that everybody reads. The biggest sellers are people who write romances and mysteries.

DL: Did you keep writing westerns?

JM: Well, I was writing westerns in Oklahoma because there was a very good western writer, Foster Harris, and he had these connections with these magazines. That is really how I got published. But I didn't know too much about westerns. For instance, I didn't know what they meant by "working the horses in the spring." So they were geldings. Geldings are easier to deal with. Stallions are very hard to deal with as a horse. So they "worked" horses in the spring. Louis L'Amour was teaching our class one day. He knew somehow I had been writing westerns and didn't know what that meant. He said I could never write a publishable western because I didn't even know what that meant. That was Louis L'Amour. He wasn't as famous then as he would become, but he was pretty famous or they would not have had him come as a guest.

DL: Did you keep up your writing when you were working at Boeing?

JM: Yes, I published a story in Art and Literature. It was a magazine listed as coming from Paris, but it was actually from Switzerland or one of those tiny countries there. John Ashberry was the editor, and he accepted my story and then he told Lynne Nesbitt, the agent, to write me for more. I sent her some stuff but she didn't think much of it. I saw John Ashberry here in New York, but he didn't know me. So I published this story in Art and Literature. That was my first literary story, in Art and Literature. I think I got a hundred and thirty dollars for that one. There were a lot of good people published in that issue. Laura Riding was in there, that Spanish Nobel prize-winning poet, Neruda. He was in there with me. There were a lot of big guys in Art and Literature.

DL: When I met you, you were retired from Boeing.

JM: For some reason, I can't remember why, I quit Boeing. Anyway. When I quit Boeing I went to work for the Wichita Eagle, and I worked for them for nine years, and then one day I didn't like what they were doing to my stories, and I just quit, so I just walked out. Then I went to work for Beech as a writer. One day I quiet Beech. I was 55 and I decided I'd retire.

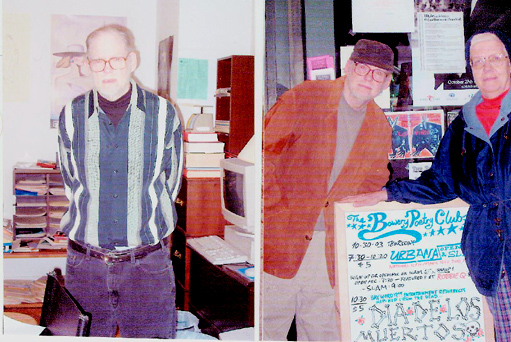

James Mechem in Caprice magazine office, East 57th St., New York City. (R) James Mechem and Ruby Baresch at the Bowery Poetry Club, NYC, Oct. 30, 2003. Photographs by Denise Low. |

DL: Did you start Caprice when you were 55?

JM: I used to have a little magazine called Out of Sight. Do you remember those ditto machines with purple ink? It wasn't as good as mimeo. I had a little ditto sheet, and sometimes I put out three of those a day. Not very often. So in order to indicate that I didn't have any set publishing schedule, I wrote on it "Published by caprice." Everybody thought "Caprice" was the publisher. People would write in and say, "Maybe Caprice won't like this, but maybe you can get it by her anyway." Then they had a little group called Women in the Arts, a local chapter, and they wanted me to join and publish a journal for them, a journal called Collage, and so I did.

DL: Who were the women in this group? Marnie Morland?

JM: Yes, Marnie helped me with that. Marnie was assigned to me to get the copy ready. That was the first time that I ever saw her.

DL: Is this the 1960s?

JM: It must have been. And then when I was doing Collage, a friend of mine, Mark Edwards, wanted to do a magazine with me, and we called that Redstart. I didn't like the way he was editing, so I said, "I'm going to every other month, we'll call it Redstart Plus," and I'd edit it. I still have some copies of Redstart Plus. But he was getting his hand in Redstart Plus too and I decided to do one completely on my own. I had just read Elizabeth Gould Davis' The First Sex. She said the first sex was women, and there were no men around. For some reason, they had a mutant and they had different kind of chromosome, and instead of 2 Xs, they had a split and there was an X and a Y. She called these first people the "ancient mariners," so I decided that would be the publisher of my magazine, and it would be called Caprice.

DL: So you've been publishing magazines since the 1960s.

JM: Oh, I forgot one of them. A friend of mine, Eddie Hullet, and I did one called The Beaters after we heard Charles Plymell was going to publish a little magazine called Now. And then he published Now Now, and then he published Now Now Now. In Now Now, I think, Ginsberg stole a couple of lines of mine for a "cutup" piece. I met Allen Ginsberg, when I was standing in a cafeteria line with him. I said, "We were trying to find you last night," and he says, "Do you want to get together now?" He was getting kind of tired of Peter. He was there with Peter Orlovsky.

DL: That was in Wichita in 1966, when Ginsberg made his sweep through Kansas. He was in Lawrence, too, but I think he was more impressed with the scene in Wichita. At least he wrote about it more.

JM: After he left Wichita he wrote "Wichita Vortex Sutra," which was published in Life magazine. A lot of the people who went out to San Francisco and became the beat renaissance were from Wichita. Charley Plymell, Michael McClure, Bob Branaman. There was a whole coterie of them, who were the crux of the beat renaissance.

DL: Did you know Michael McClure well?

JM: Not well, but we went to see him at his house once. I sort of hung out with Charley Plymell sometimes, but not with the other guys. Where I got that name for my little ditto sheet, there was a woman there Connie, that was her favorite phrase "Out of sight." It was the first time I had heard it. There was probably a place called that.

DL: Why do you think so many beats came out of Wichita? Of all places, why not Ft. Worth or Des Moines or Fargo?

JM: A lot of them did come out of Des Moines. That was the first writing workshop I went to, at Drake University. Wichita was a kind of a mixture. For instance, there was a lot of construction and building going on in the just before the war, when the aircraft plants were needing people. So there was a great demand for housing. A wealthy class sprung up, from real estate, construction, and all that. That was one of the things that made Wichita the richest city in Kansas, richer than Kansas City, Kansas, or Topeka. And another element of Wichita was all of these people who came in from Arkansas and Oklahoma who came in to work in the airplane factories. And then there was another wealthy element-the oil. There were oil fields all around Wichita. El Dorado was nothing but oil fields all around there. And the oil-there was a lot of money in there, which makes Wichita kind of a strange amalgam.

DL: And it's always had an arts community

JM: Yes. The woman who bought art for the Wichita Art Museum came to New York all the time. She was very conversant with New York. And she had incredibly good taste. She knew the people in New York. She bought the art works and brought it back to Wichita Art Museum, and people don't realize how good the museum really is. I can't remember her name. Plus you know how the art association museum started? The Art Association on the east side? The art museum was owned by the city. But the movers and shakers who ran the art museum were private individuals with money and they didn't go along with some of the policies of the city. So they were going to make a museum of their own. So they went together and they bought the land and built the art association out on the east side.

DL: And that was all women, wasn't it?

JM: Yes, I guess so. That also helped the arts community in Wichita, which is another factor.

DL: Was Charley Plymell from around Wichita?

JM: Yes, they lived on the west side growing up. His mother, during the war when they needed women to work, his mother became one of those people who climb up in the trees and prune. They were needing highways built through town, and they didn't have any men, and Charley's mother did that. I talked to her. I heard about her and I went out and talked to her a couple times because she was so interesting. She was tough. She talked tough, acted tough. She wasn't too tall, naturally. But she was an interesting character and you can imagine how Charley turned out the way he did. I think his father left the family even before the war.

His father was a millionaire three times and lost it all three times. But Charley's family always called him Chuck. He was always Chuck to anyone who had known him as a kid.

DL: Did his mother work during the period the Kansas turnpike was being built? The early 1950s.

JM: That must have been it. She was a character. You should have heard her. Michael McClure was from there, too. There were several artists, who are famous artists now. They are in New York now.

DL: Why did you keep doing magazines? You started in the '50s with ditto machines, so this makes your sixth decade.

JM: I got started early. In junior high school I was editor of our school newspaper, called the Rough Rider. In college I was supposed to go to University of Iowa because they have a good writing school, but they also have one of the best art schools in the country. The art school was on the left bank across the river from the rest of the university. It was such a good school that I took more art classes than I did writing classes. I really liked design. I think I should have been a designer more than a tech writer, because I really like d designed. I took several classes in printing and graphic design. I loved graphic design. That has always been my real love. Doing a magazine is kind of graphic design. People nowadays, the reason they say they like Caprice is because it's hand done. I call it old-fashioned. That's what people say about it, since it is not done on a computer.

James Mechem at breakfast the morning of his 80th birthday, Oct. 31, 2003. "He is very Scorpio." Photograph by Denise Low. |

DL: Who works on it now?

JM: Arthur Winfield Knight writes movie reviews and Ruby Baresch writes some movies reviews of the festivals and Marge Piercy always sends me something about two or three times a year. Have you seen a recent issue?

Carol Bergé is new. Lynne Savitt is still my co-editor. She sends me something every issue. She and I have been on the cover more than anybody else. That's about all. I do most of the work myself. Janet Eidus, I see her every once in awhile. She used to send me some stuff but I don't think I've heard from her in a long time.

DL: How do you distribute it?

JM: I don't. I send it to the staff and the contributors and I send it to the few subscribers. I've never had more than 30 subscribers. I don't like a lot of subscribers. I used to. With Out of Sight I said it was $100 a year, or a series. The series were not always annual. Then I had Caprice at $50 a year because I didn't want a lot of subscribers. But now that I've cut it down to three times a year I decided I can't get by with that much, so that's why it's only $25 now.

DL: So you still cut and paste it and everything? Do you take it to a Kinkos?

JM: I send it to my printer in Wichita, Independent Printing. Brent used to publish it, and I copied it. One day I just put "Printed by Brent" with a space after it. They've changed printers, but I put in the printers name like that. Now it's Laurey.

DL: How did you meet Marge Piercy?

JM: She came to read in Wichita. Mardy Murphy and I did our series one year of big writers to speak at Wichita and we got the city to fund it. Marge Piercy was one of the ones who came to read there. We were sitting in the front row right beside a guy who was heckling her, and she said, would somebody get this man out of here? So one of the ushers came and took the guy out. At the reception afterwards we asked Marge if she wanted to go out to dinner with us, and she told us no. But then when we took her to the airport, she saw us at the airport and apologized. I didn't realize it was you guys, I thought it was the heckler. Ever since then she's been real nice to me. She sends me stuff. She came to read several times in Wichita after that, and she didn't recognize me. She still corresponds, but she doesn't know who I am.

DL: How many people do you correspond with?

JM: I don't really carry on correspondence with anybody, but every once in awhile when I'm short of material I send out these cards. But lately, this last six months or so I have been on the internet email. I correspond about every night with Lynne Savitt. I have the cheapest internet service. When I'm online no one can call me.

DL: One electronic device at a time is plenty. And by the way, happy 80th birthday in two days.

(Interview and photographs © 2003, Denise Low, Kansas Poet Laureate 2007-2009; Beats In

Kansas © 2004, George Laughead)